Actuarial Career Success: 40 Little-known Tips and Ideas

1

Sculpting an Actuarial Career Takes Time: Don’t Sweat It

In the summer of 2022, whilst on holiday in England, I happened to walk past the house I lived in when I started my actuarial career.

First time back in 22 years.

Walking past that dingy basement room in a rundown House of Multiple Occupancy it struck me that I’m in a completely different place now than I imagined when I started my actuarial career in consulting back then.

I never imagined my future actuarial career would be a mixture of lecturing/researching actuarial science in academia and building a digital actuarial business (ProActuary).

Back then—young, naïve and hungry for success—my plan was to qualify as an FIA actuary in 3 years (it took a lot longer!), become a Scheme Actuary (decided against it) and make lots of money (I had 3 kids instead!).

The reason I bring this up is not because I think I’ve now figured things out but because my academic job and ProActuary business involves speaking with lots of new trainee actuaries. I therefore get insights into problems new actuaries often face as they embark on their new actuarial careers.

Occasionally I hear about concerns that their actuarial career isn’t panning out as they expected. Or they aren’t enjoying their role as much as they thought they would.

Part of the problem, I believe, is often an expectation issue.

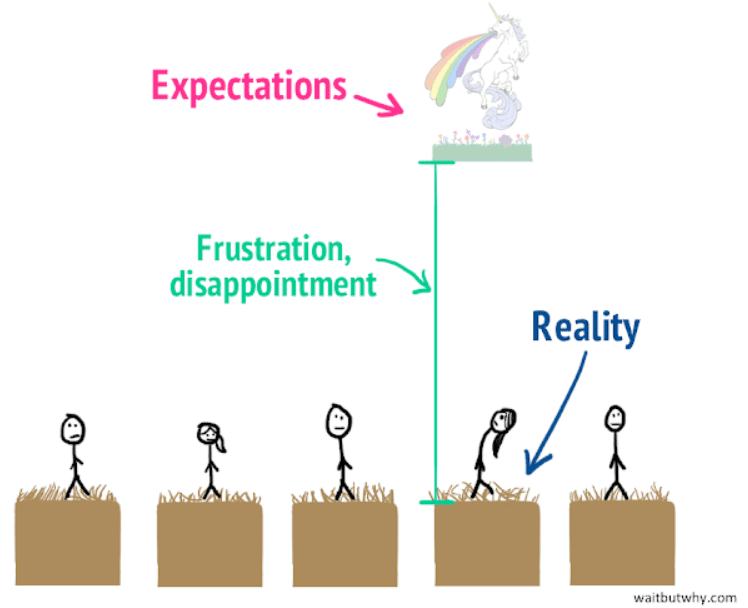

Career expectations can be a dangerous game. As Tim Urban puts it in his fabulous WaitbutWhy blog diagram, it can create a dangerous gap between reality that eventually results in frustration.

Image Source: WaitButWhy

The thing is, it usually takes time to sculpt your actuarial career to match your interests. The road is not a straight path. Instead, in our ever-changing, fast-paced world it looks something more like this:

Yes, people can strike it lucky and start off in their dream actuarial job or role perfectly matched to their strengths and personality. But generally – at least from my experience – navigating towards your actuarial career ‘calling’ involves a lot of introspection and trying new things (i.e. taking risks and probably failing somewhat).

Figuring this stuff out is hard.

But, given the ever changing world of opportunity we live in, I do believe for most people an actuarial career of purpose, fulfilment and opportunity is definitely possible.

So instead of thinking you have to have your actuarial career all mapped out from the outset, here are 4 ideas:

1) Recognise that actuarial career planning is an ongoing iterative process that needs to be actively managed in a flexible way.

It’s never ‘done’. We never truly get there. Instead, it’s a squiggly, and oftentimes downright messy, path of iterating towards fulfilment over time.

Hence I humbly suggest, if you are new to the actuarial field and trying to figure out your own actuarial career path, you should get into the habit of constantly asking yourself questions and thinking about where you want to go and why. See it as a voyage of discovery.

Example actuarial career questions:

- What am I good at?

- What drives and motivates me (not always obvious)?

- What do/don’t I enjoy?

- Who do I enjoy being around? Why?

- What gives me energy? What drains me? How can I create more of the things that energise me?

2) Think in terms of transferable skills, adaptability and being able to reinvent yourself at will.

These will become increasingly important in the future for your actuarial career as the business landscape changes and in particular as AI becomes further embedded into actuarial work and careers in general.

3) Keep a close eye on trends.

What direction is the world heading? What will it mean for the supply/demand, and hence market price, of actuarial skills you have/can potentially gain?

4) Take active ownership of your actuarial career.

Don’t rely on your employer to dictate everything about your actuarial career path. Instead be proactive. Can you position yourself to catch future luck?

Yes, there is value in planning ahead and setting goals.

But destiny has its own path.

New trainee actuaries should let the words of Yuval Noah Harari truly sink in…

“We are in a unique situation in human history when, for the first time, we have no idea what the job market will look like in 20 or 30 years. That was never before the case in history.”

2

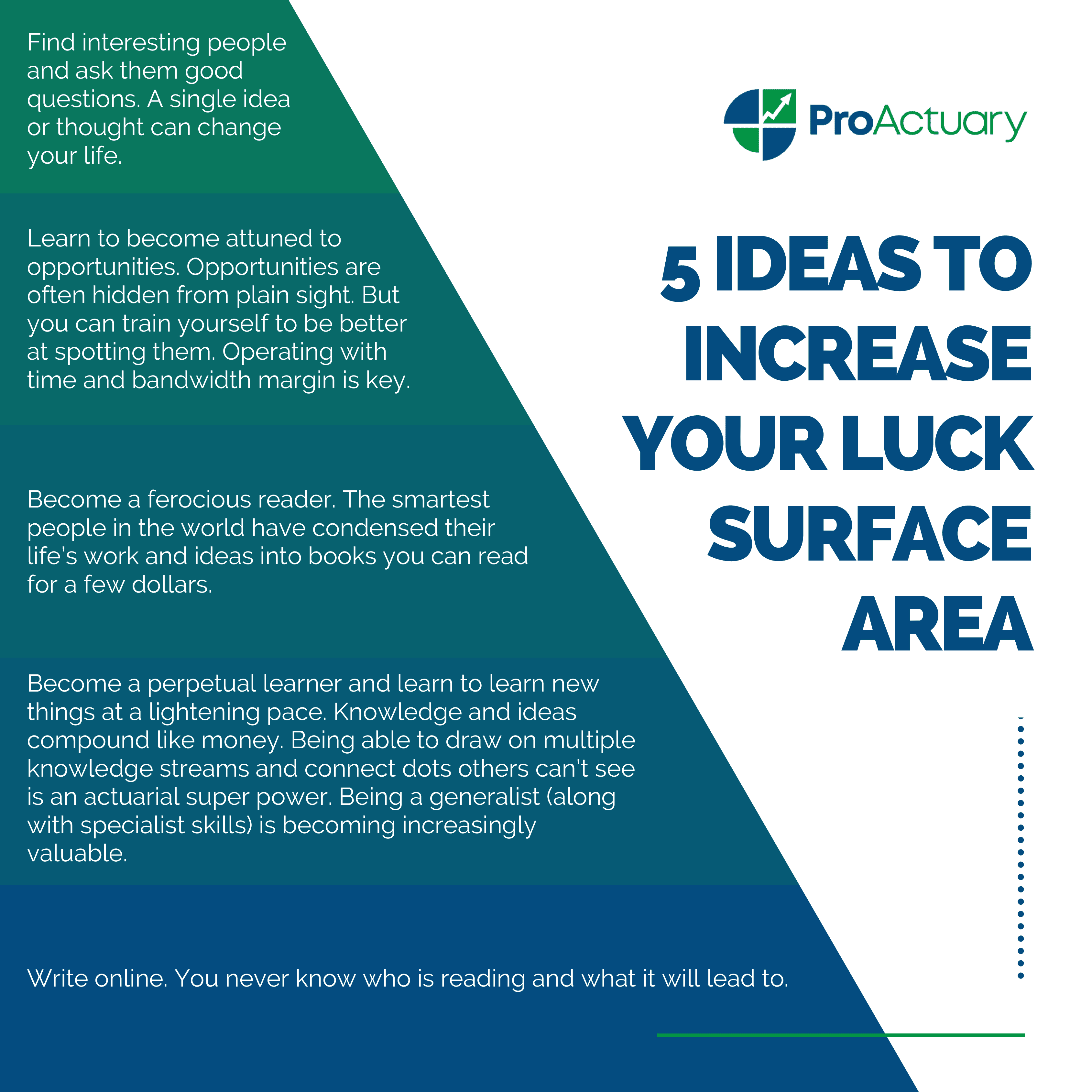

Increase Your Actuarial Career Luck Surface Area

Advice I wish I’d received as a younger actuary:

Do things to increase your luck surface area. Constantly look to push probability edges in your favour when possible.

5 ideas:

Every interesting conversation you have, book you read or presentation/piece of writing you put out there is like a small bet. You never know what upside might result. Where your actuarial career might go as a result.

To give you an example, the other day I posted on LinkedIn about ProActuary. Less than an hour later an FIA actuary messaged me asking if he could help in a volunteer capacity.

That wasn’t my intention with the post. But it was a valuable serendipitous event that came about through a small action (online writing=bet) that increased my actuarial career luck surface area.

Similarly, our ProActuary Advisory Board came about mainly from chance interactions from online writings leading to connections and conversations.

We’ve since had the privilege of getting regular valuable advice from some of the brightest minds in the actuarial space.

Luck, from the outside, may seem completely random. But often that’s not the case.

Being proactive in key areas and having the personality trait of taking small risks (making small bets) will help increase the probability that you ‘catch luck’ in your life and your actuarial career.

“Luck is rarely a lightning strike, isolated and dramatic. It’s much more like the wind, blowing constantly. Sometimes it’s calm, and sometimes it blows in gusts. And sometimes it comes from directions that you didn’t even imagine.”

– Tina Seelig

3

Systems Over Goals

At ProActuary, we have organised a number of large global actuarial virtual summit events. The Digital Actuary in 2020. The Growth Actuary in 2021. The Disruptive Actuary in 2022. 3 big global events. Over 10K attendees from 75+ countries and more than 60 speakers.

So what’s been our secret sauce, allowing us to pull this off?

A big part has been an obsession over processes and systems.

Such as:

- A Trello board using a Kanban system allowing 200+ tasks to flow from “to do” to “in progress” to “done”.

- Pabbly triggers that automate workflow automations and allow our tools to seamlessly ‘talk’ to one another.

- Email sequences that go out with minimal effort.

- RPA robots that perform manual tasks with ease.

- Airtable forms where speakers and partners can submit information 24/7.

- Excel macros that organise data at the click of a button.

ProActuary is a tiny little company.

No army of volunteers. No massive unlimited budget. No marketing dept.

To achieve big things with limited resources requires leverage.

One of the key ways we obtain leverage at ProActuary is via this obsession with systems and processes.

The background question behind every series of tasks is always, “Can this be automated, streamlined or simplified?”

Processes and systems can be implemented in almost every aspect of your life.

From actuarial study to healthy habits to your everyday work and general actuarial career.

I truly believe this mindset is one of the biggest leverages you can create in your actuarial career. And will become increasingly valuable.

I like how James Clear thinks about this:

“You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.“

How can you use processes and systems to create leverage in your own actuarial career?

4

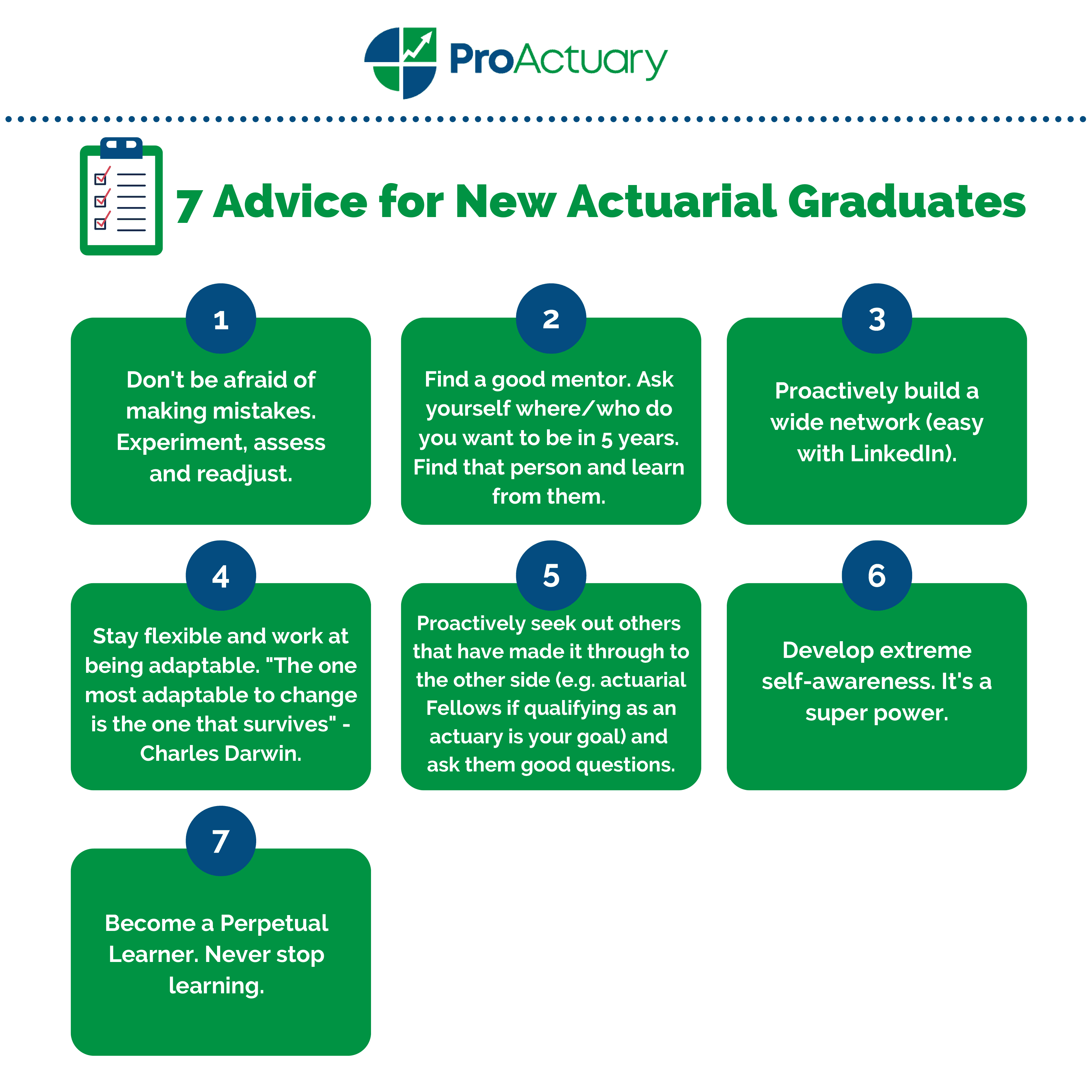

Actuarial Career Advice for New Actuarial Graduates

I’ve taught hundreds of actuarial students over the last 14 years.

They are always talented and dedicated students and many of them go on to have very successful actuarial careers.

New Actuarial graduates hear lots of actuarial career advice as they leave university. If you are entering the actuarial profession, here are my top 7 pieces of advice to think about as you embark on your future actuarial career:

Edit: I nearly forgot what I consider to be perhaps ‘the most important’ piece of advice:

Do not put your actuarial career before your health.

Yes, you may have to occasionally work late nights and sacrifice sleep. Yes, there may be stress at times. BUT if this is a constant and ongoing way of life in your job, then rarely (if ever) imho is the trade off worth it.

Those old sayings such as “your health is your wealth” have stayed around for a reason. They have a lot of truth in them.

Good luck to all the new actuarial graduates out there starting out in their actuarial career!

5

Actuaries Can’t Always Predict the Future

I wrote this “Last Actuary” essay in 2017.

It sat on my hard drive for 3 long years.

Didn’t think it was any good.

Then, in 2020, I noticed a Society of Actuaries competition for essays on ‘Actuarial Innovation and Technology.’

Seemed a nice fit for my Last Actuary rambling.

But again, I thought there was no way it would be worthy of anyone’s time.

No one would want to read it.

So I decided not to bother.

The hard drive was its rightful place.

Safe.

Away from critique and judgement.

A few hours before the competition deadline, something made me change my mind.

Can’t remember what.

Might have been the faint feeling of shame of not even trying. A writer that wrote but was afraid to share.

So I opened the laptop, sitting on my cramped desk in my makeshift home office, and emailed the SOA my entry.

Like magic, it travelled all the way from Ireland to the US, in milliseconds.

Then I promptly forgot all about it.

Until one day, out of the blue, the SOA emailed to say they were publishing it in their report, along with another entry I had submitted.

They were even sending a prize. $5,000.

I’d never seen a $5,000 cheque before. Felt strange. Academics are more used to the bizarre practice of paying for the privilege (!) of having your work published.

Maybe that does make sense.

Just not to me.

It turned out that people liked The Last Actuary.

I received nice messages, from actuaries around the world, telling me they found it “fascinating,” “thought provoking” and “insightful.” It even received an SOA “Honorable Mention.”

I liked hearing those big words. They made me feel good.

The ego was safe. For now.

But more importantly, it reminded me that even actuaries can’t always predict the future.

Especially about oneself.

6

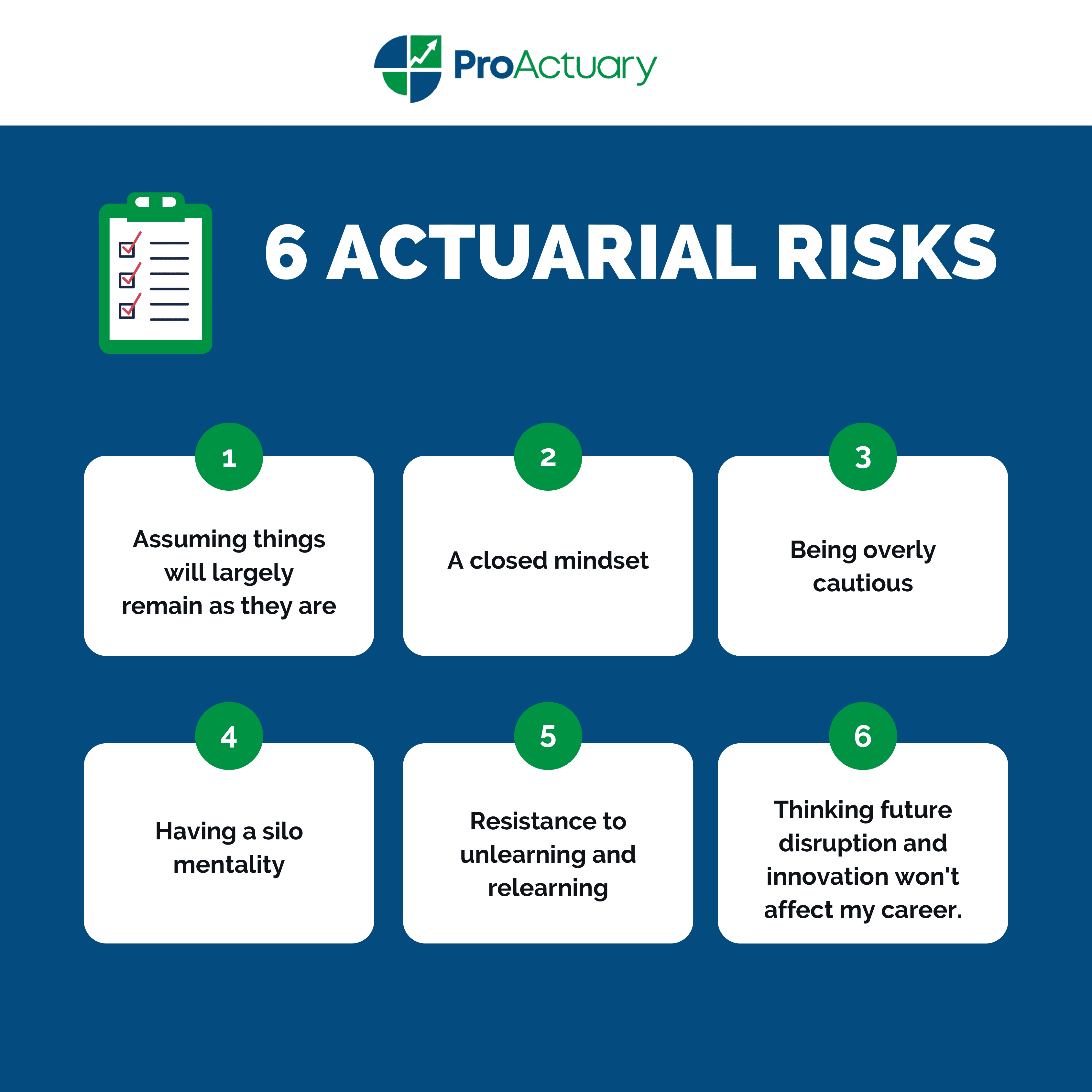

Actuarial Career Risk!

Actuaries deal with risk. Here’s what I think is risky when it comes to your actuarial career:

7

Actuarial Models: Invert Always Invert

The most useful model I learnt when I was a trainee actuary, starting my actuarial career, was not a financial model.

It was the mental model of inversion.

Thinking deeply about what could go wrong in my future life. And then taking steps to fix that.

This goes deeper than simple risk management.

It’s about opening your mind to different ways of thinking.

Approaching problems from a different angle.

Turning things upside down by considering what you need to NOT DO (or avoid) instead of just thinking about what you need to do.

A pre-mortem to search for possible threats.

Take your actuarial career:

Imagine it’s 2031.

You’re dissatisfied with your work. You don’t earn as much as you want. Your day to day tasks don’t excite you. Every day is the same. Companies and recruiters ignore you.

Take a moment to really imagine that. See yourself in that position in 2031.

Now step back and try and imagine what went wrong?

How did you get there?

Was it:

- Complacency with your actuarial career?

- Lack of discipline?

- Playing it too safe?

- Not looking after your health and burning out?

- Not embracing new actuarial career opportunities?

- Foregoing learning (important but not always urgent) for other stuff?

Whatever you come up with take steps to fix that.

Now.

“Invert, always invert: Turn a situation or problem upside down. Look at it backward. What happens if all our plans go wrong? Where don’t we want to go, and how do you get there? Instead of looking for success, make a list of how to fail instead. Tell me where I’m going to die, that is, so I don’t go there.”

– Charlie Munger

8

Frank Redington Actuarial Career Advice: More Than an Actuary

One of the most legendary actuaries of all time: Frank Redington.

In 1968, he famously said:

“An actuary who is only an actuary is not an actuary .“

But what exactly did he mean?

Here are my 7 top interpretations:

Self-awareness & Emotional Intelligence

There’s a running joke that an actuary is a computer with a heart.

Only 43.64% of that is true.

The ability to understand our feelings and act accordingly without impulsivity is an important trait. Self-awareness is one of the most valuable qualities an actuary can develop for their future actuarial career.

Judgement & Intuition

An actuary’s world and career involves numbers, math, statistics, prediction and forecasting.

But numbers don’t always tell the full story.

We need to look beyond the numbers.

Exploring other similar fields, reading widely, thinking holistically and talking to people in other domains can help us connect the dots.

Communication

It doesn’t matter how good our technical analysis is if we can’t communicate the results in the right way to the right audience at the right time.

It’s Not About the Techniques and the ‘Tools’

To quote Frank:

“The actuary’s danger may lie in too close preoccupation with his particular techniques … It is not the tools he uses which make a great craftsman. It is the way he feels and thinks.”

– Frank Redington

Perspective

If you are just your work, something’s wrong. Family, friends and health supersede work.

Flexibility & Adaptability

Actuaries are now faced with the very real idea that they may undertake future work and embark on an actuarial career that is completely different from their current role and envisaged actuarial career path.

We need to have the ability to adapt to the needs of the changing business environment and apply our skills and knowledge in new domains and ways.

Creativity

As the world shifts in a progressively competitive and global way, the ability to challenge ideas and come up with new unique solutions is becoming more important.

Future actuarial careers will involve coming up with new unique ideas that embed new technologies and ways of thinking.

This is likely to be especially true as we bring new exciting products to the insurance consumer (think wearables, IoT, telematics etc).

Innovation is one of the key ways by which we can remain in business, and creativity is the gateway to this innovation.

9

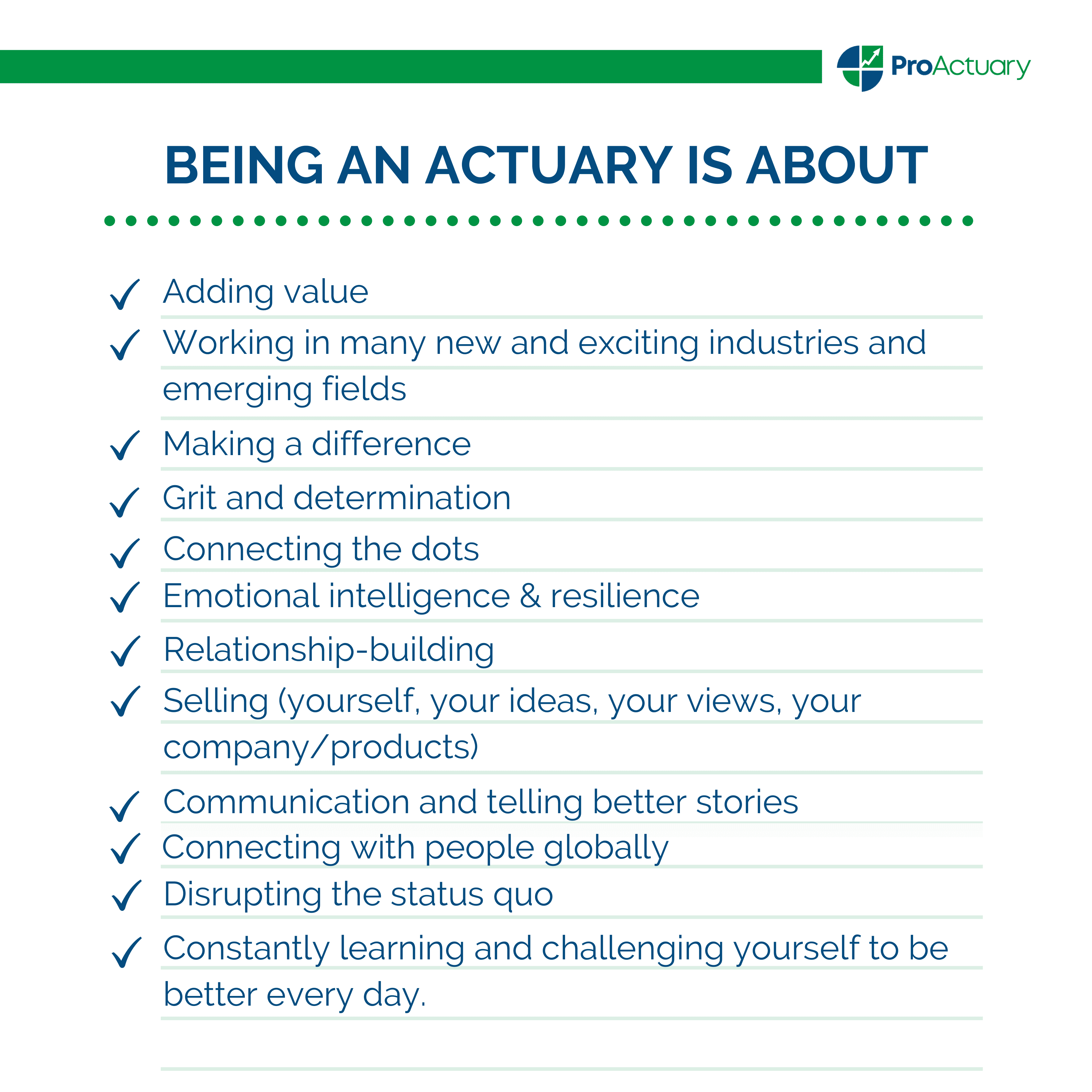

What is an Actuary Anyway?

I used to think an actuarial career was all about:

- Passing exams

- Making money

- Numbers

- Working in insurance or pensions

- Technical knowledge alone

Now, I increasingly think being an actuarial career is about:

10

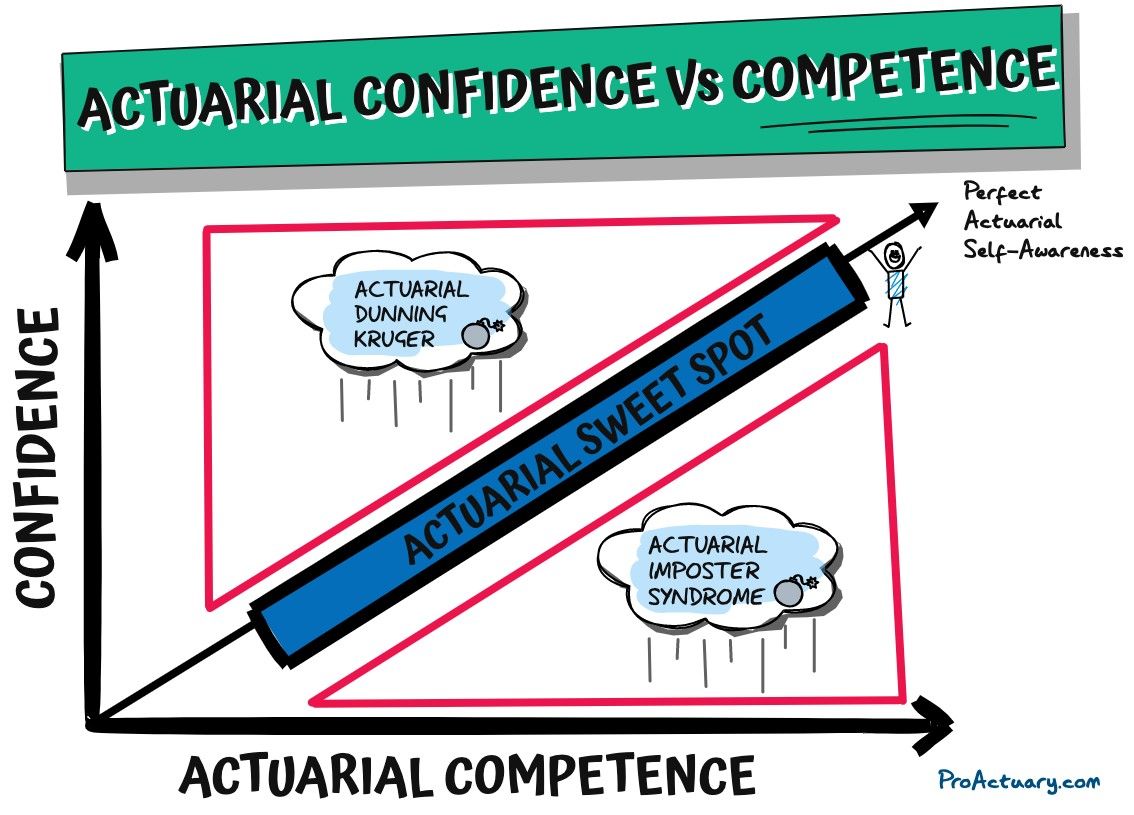

Actuarial Confidence Vs Actuarial Competence

I know I could relate to this at the beginning of my actuarial career:

Are actuaries more likely to experience imposter syndrome or the Dunning-Kruger effect (overestimating ability)?

Or, do we generally sit perched on the sweet spot of ‘confident humility’?

You’ve probably met people who fall below the sweet spot line stuck in imposter territory.

Or maybe you’ve been there yourself?

Feelings of not being as competent as others perceive you to be, and that someday you will be ‘found out’.

Entering the field and starting my actuarial career with a Loughborough University Sport Science degree, having never touched an Excel spreadsheet, and working/studying with Oxbridge grads with 1st class Maths degrees, imposter syndrome was an unwelcome experience.

Then we have those with confidence stretching well beyond their ability.

Riding high in the grand illusion of a perceived ability that exceeds their actual competence.

Thinking about actuarial science specifically, I believe the actuarial qualification can potentially pull you in both directions:

The profession is filled with intelligent people. When the bar gets raised by your surrounding peers, it’s easy to feel inferior and to doubt your own ability.

Then we also have actuarial personality traits in the mix:

Actuaries are more likely to be introverted and to have perfectionist tendencies (from my experience).

Both are strongly correlated with imposter syndrome.

On the other side, the long, difficult and rigorous qualification process can leave you coming out the other end feeling like you know a lot of ‘useful stuff’.

The large bank of knowledge, obtained through blood, sweat and tears, can easily pull you over the bar of optimal self-awareness into the realm of an inflated perception of ability.

I believe there are potential actuarial education implications off the back of this question.

In my humble (but not too humble!) opinion, all aspiring actuaries should:

- Recognise the importance of “confident humility” as an important actuarial attribute to diligently work towards during their actuarial career.

- Develop an appetite and appreciation for proper value additive and ongoing learning (not tick box CPD compliance).

- Seek cross disciplinary collaboration and engagement, during their actuarial career, as well as actively seeking out opinions from other subject matter experts to fact check and to test assumptions.

- Learn how to re-frame certain thoughts (e.g. replace “I’m not as good as others” with “I’m on a personal journey of learning”).

- Actively seek out good mentors to expedite your actuarial career. Having someone you can share feelings with and challenge your thinking is a great way to gain clarity and perspective.

- Develop a habit of continually asking yourself good questions such as: “What is the evidence to support this?” and “What faulty assumptions could I be making here?”

- Actively seek feedback on your actuarial career and view it as a gift!

The overarching antidote to both the Dunning-Kruger and imposter syndrome pitfalls is, of course, self-awareness, which I believe is one of the most valuable traits an actuary can develop for a successful actuarial career.

11

Books For Actuaries

Learning, for actuaries, never stops, right?

Here are 9 books I believe every aspiring actuary should read for their actuarial career:

4. Financial Enterprise Risk Management

This helped me so much with my PhD I had to mention it. The author Paul Sweeting is a well-known actuary in the ERM field and he writes with clarity, making the subject come alive.

If you are aspiring for the CERA qualification or just want to enhance your ERM knowledge, for your actuarial career, this should top of your list.

5. Ultimate Guide to Business Writing: All the Secrets of Creating and Managing Business Documents

Communication is becoming increasingly important for a successful actuarial career.

If we can’t communicate our results, does it matter how technically brilliant they are?

Julian Maynard-Smith was a speaker at one of our ProActuary conferences and he did a great talk on the subject. He has helped actuaries to produce and manage their actuarial, risk and compliance documentation, as well as running writing courses for actuaries.

Personally, I think writing well is one of the most underappreciated skills you can learn for your actuarial career.

6. Getting Things Done

Managing your life well, staying productive and learning to create trusted systems is a big lever for advancing your actuarial career.

The classic book by Dave Allen will help.

It had a profound impact on the way I think about and manage the work inputs flowing into my life when I read it nearly 20 years ago.

9. Mindset

The opening talk on our ProActuary Growth Actuary conference was “How to develop a Growth Mindset as an Actuary.“

Over 3K people registered. We weren’t expecting such interest!

It seems the actuarial profession is embracing the powerful ideas around a growth mindset…and with good reason!

The author, Carol Dweck, is a leading researcher in this area. Highly recommended.

12

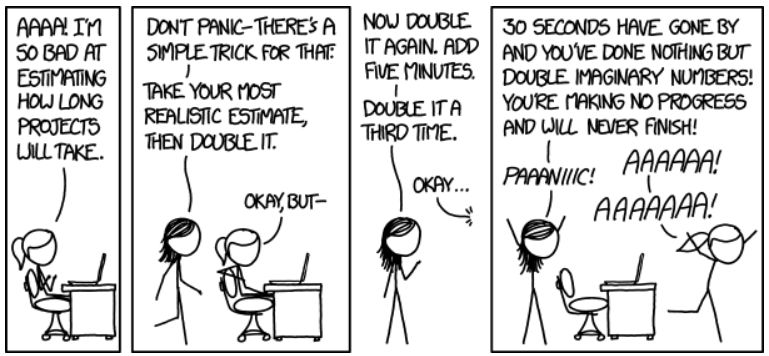

Actuarial Time Management: Hofstadter’s Law

As an actuary I’m meant to specialise in making predictions.

Yet I often repeatedly fail at predicting how long a project will take to complete.

Enter Hofstadter’s Law:

“It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.”

– Douglas Hofstadter

Thank you Mr Hofstadter for making me feel better about this.

Image source: explainxkcd

13

Perpetual Learning

“It doesn’t get easier, you just get faster”

– Greg LeMond

This was an old saying that was always at the forefront of my mind when I was training for cycling races. I think actuaries should apply the same idea to our pre/post qualification training and general actuarial career:

“It doesn’t get easier, you just get better” Are you a perpetual learning actuary?

For the sake of your future actuarial career, I hope so!

14

Tips for a Better Life

Great “tips for a better life” for actuaries from Ideopunk on LessWrong:

15

Probabilistic Thinking

Actuarial Science helps to tune our skills in math and logic, improving our ability to think in a probabilistic fashion.

I believe the ability to accurately attach probabilities to events in our lives is one of the most useful skills we can learn, to help make accurate decisions.

However, as humans, we tend to struggle with rationality and objectivity. Our views and outlook are coloured by our very limited experience.

Nassim Taleb’s Black Swan metaphor highlights how our worldview and belief system (e.g. probability attachment) can be mistakenly altered when living through the experience of impactful and surprising events.

As Taleb warns, it’s easy to rationalise an event after it happens. We start to see all the reasons why we should have seen it coming. Often without realising, we have updated our mental model with an over-egged probability.

Like the gambler who succumbs to the fallacy of seeing patterns that aren’t there and dots that don’t exist, it is easy to mistakenly colour our future expectations with random or erroneous past data.

The danger here is that we then place too much emphasis on mitigating similar risks (to what we have personally experienced) in the future. And given risk is everywhere in life, we then have the risk of an opportunity cost of potentially not dealing with other risks where we should instead place our focus on.

Risk is everywhere. Risk is unavoidable. The question is: in a world of limited resources, imperfect information and hindsight bias, how can we optimise our approach to risk taking in our lives? Becoming better at probabilistic thinking can help to ensure we spend our resources wisely, by focusing on embracing and mitigating the right risks.

An actuarial career helps us to develop this valuable life skill.

16

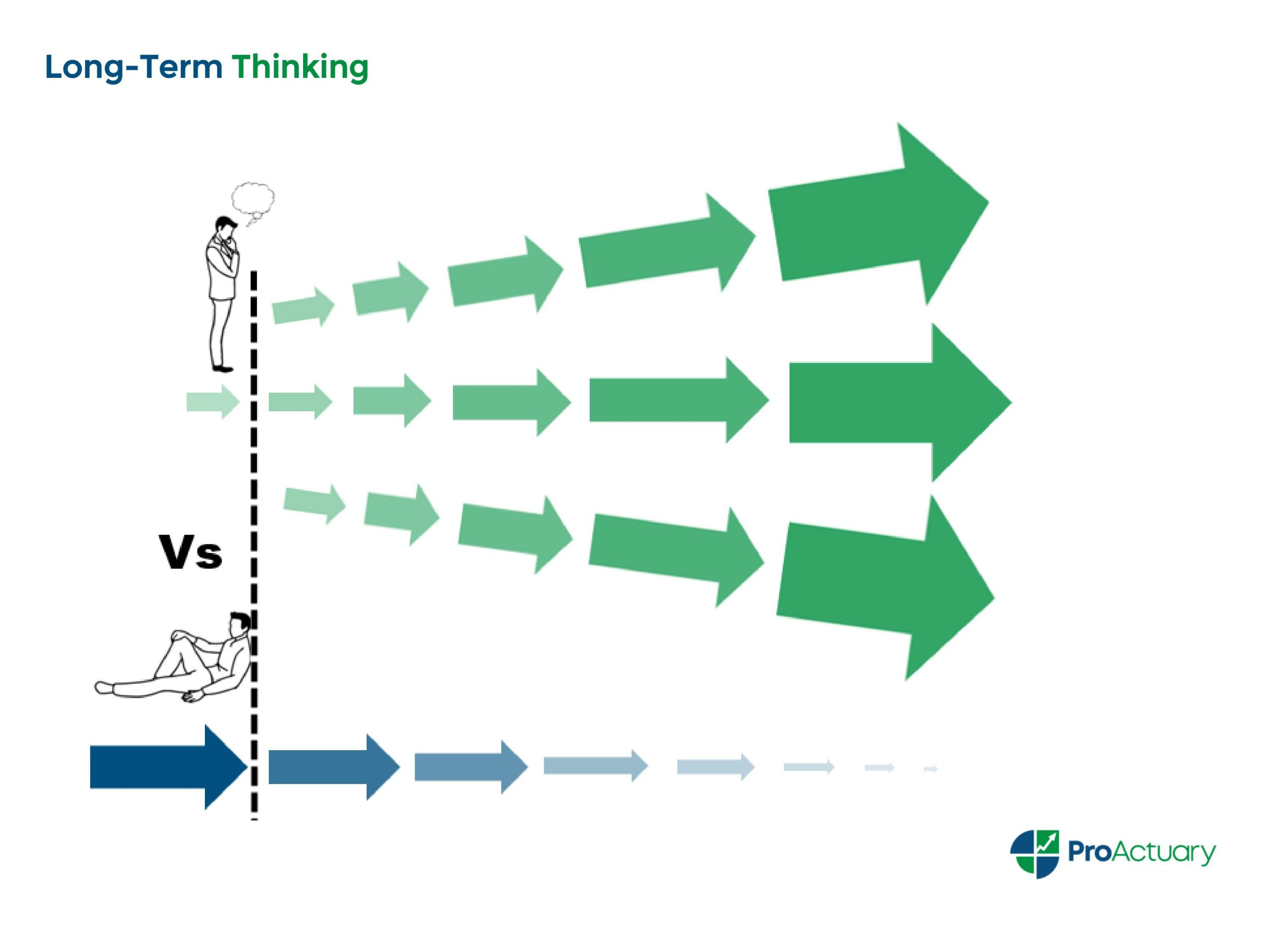

Long-Term Thinking

One of the most useful things I’ve learnt studying and practicing as an actuary and during my actuarial career is long-term thinking.

As financial fortune tellers, actuaries focus on the future. We need to consider cash flows many years down the line.

I’ve found this embeds a neurological imprint where you start to also naturally view other aspects of life through a long-term probabilistic lens.

It becomes easier to engage in the difficult task of second or higher order thinking.

Long-term thinking can and should be applied to many areas of life. For example finances, health and your actuarial career.

With an actuarial mindset, personal decisions are made in the context of longer term implications, where you start to naturally consider all the future benefits (assets) and consequences (liabilities) of your chosen path – each with their own probability attached that you intuitively discount back from the future to the present.

In essence, it becomes easier to imagine how your future-self, possibly many years down the line, might benefit from your actions or in-actions today.

We all make sub-optimal decisions in life. Yet if we can train ourselves to think long-term, which I believe an actuarial career helps with, then we have a powerful life tool providing an edge towards better decision making.

17

The 4 Ds of Actuarial Time Management

The 4 Ds of task/time management to use every day in your actuarial career:

Or should it be: Delete, Delegate, Defer, Do?

I’m increasingly of the belief that many of us (myself included) tend to get the weighting of these things wrong, with regard to the tasks that make their way into our lives/inboxes.

Not giving enough thought to which of these four categories our tasks should fall under.

Shuffling paper, responding to emails and ticking off minor to-do list items feels good, but rarely move the needle.

“It is not enough to be busy. So are the ants. The question is: What are we busy about?”

– Henry David Thoreau

18

Actuarial Creativity

I stopped cycling and running for a few weeks.

Life got busy.

The emails just kept on coming. And the “todo list” just kept on growing.

But, I got back on the bike.

And you know what:

I had more creative thoughts and ideas during my one hour bike ride than I’ve had whilst “working” solid for the last 2 weeks.

It was a good reminder for me, that no matter how busy you are you, you shouldn’t neglect the fundamentals.

Kind of reminds me of the old Zen proverb about meditation (I view cycling as a kind of meditation):

“You should sit in meditation for twenty minutes every day – unless you’re too busy; then you should sit for an hour.”

19

Actuarial Storytelling (Part 1)

“No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.”

– Daniel Kahneman

I really like this comment by Nobel prize-winning psychologist and economist, Daniel Kahneman.

I think actuaries, like many other professionals, can be susceptible to the curse of knowledge and prone to assuming everyone thinks about probabilities in the same way we are trained to do so.

We often don’t realise that many people (as Kahneman discovered when advising Israeli intelligence in the 70s) naturally treat low probability outcomes as impossible and high probability outcomes as virtual certainties, by rounding down or up.

Kahneman’s solution to this problem was to create narratives to help contextualise and highlight how the low probability events could occur.

In other words, stories can be used to help people grasp the true essence of probabilistic outcomes.

20

Actuarial Storytelling (Part 2)

Can actuaries learn from stories?

I believe so:

A husband watches his wife prepare the Christmas ham by cutting the ham in half lengthwise (parallel to the bone) and then putting the two halves in a shallow roasting pan:

“Why do you go to the trouble of cutting the ham lengthwise that way?”

Her reply:

“I don’t know. I got the recipe from my mother and we’ve always done it that way. She’s coming for dinner tomorrow, let’s ask her.”

Christmas Dinner the next day:

“Mother, you know that recipe for Christmas ham? Why do you go to the trouble of cutting it lengthwise that way?”

Mother-in-law:

“I’m not really sure. I got the recipe from my mother, and we’ve always done it that way. Let’s ask her at the nursing home, later.”

At the nursing home:

“Grandma, you know the recipe for Christmas ham? Why do you go to the trouble of cutting it lengthwise that way?”

Grandmother’s reply:

“Well, back in the thirties, when I first came up with that recipe, we were too poor to afford a big roasting pan, and we had to cut the ham in half in order to make it fit into the pan we did have.”

Are there any outdated assumptions, technologies and techniques we are routinely using in actuarial work (I’m looking at you Excel!), without questioning, because “we’ve always done it that way“?

21

Communication

Clear communication and understanding is crucial in actuarial work.

If I was employing an actuarial student, one of the things I would look for is the confidence to clarify instructions when necessary:

Engineers at an aerospace company were instructed to test the effects of bird-strikes on the windshields of military jets.

To simulate the effect of a bird colliding with an aircraft, the test engineers built a powerful gun, with which they fired dead chickens at the windshields. The simulation worked proving the suitability of the windshields. Another test laboratory was involved in assessing bird-strikes on the windshields of new very high speed trains. The train engineers, hearing this story, set about building their own simulation. The simulated bird-strike tests on the train windshields and cabs produced shocking results. The supposed state-of-the-art shatter-proof high speed train windshields offered little resistance to the high-speed chickens, smashing every test windshield. The horrified train engineers were concerned that the new high speed trains required a safety technology that was beyond their experience, so they contacted the aerospace team for further advice. The brief reply came back from the aero-engineers: “You need to defrost the chickens….”

22

Actuarial Tools

I grew up on a farm in a remote part of Ireland.

I love going back there as it’s an opportunity to build stuff, roam the fields and just potter about with no schedule or agenda.

With patchy WiFi and no one in sight, it provides an extreme form of digital detox. An oftentimes much needed reset for the soul.

There’s an old half ruined dwelling house that my grandparents lived in. Now and again we discover things in there, or buried in the nearby fields. Here are some of the old “tools” found over the years.

Imagining my grandparents, and those that came before them, using these old tools makes me think about the tools and leverages we now have at our disposal in our modern day work.

- A high spec PC, 2 monitors and a good typing speed allowing you to work efficiently and in flow.

- Advanced data and statistical analysis using tools such as Excel, R and Python.

- Communication and collaboration via email, Dropbox, G Suite and of course Zoom/Teams.

- Networking via LinkedIn, Twitter, Meetup and Slack.

As actuaries I believe we should always seek to optimise our toolkit and levers.

AI is changing the world. tools are becoming more important and in my opinion an actuarial career will increasingly involve being able to choose the right tools and use them in the most efficient manner to manage risk.

23

Actuarial Career Reputation

I recently mentioned to some of my graduating actuaries how the actuarial world is small and hence reputation is extremely important for your future actuarial career.

It’s one of the things I like about the actuarial profession. It’s small, niche and unique.

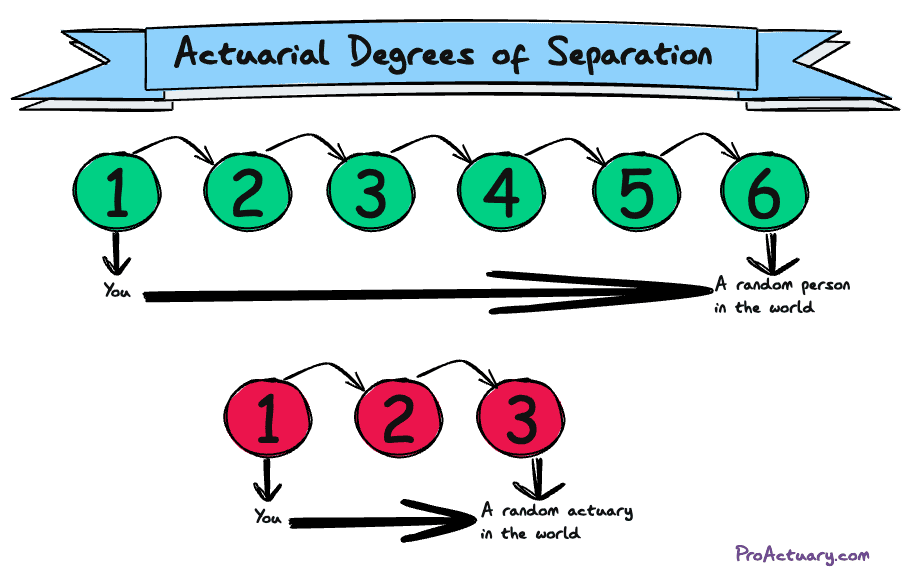

Joining it almost feels like you have entered a global family. There’s a common bond (especially when you go through the pain of a long arduous exam system) and the ‘degrees of separation’ idea is drastically reduced.

The global ‘6 degrees of separation’ drops to 3 degrees when you are in a small pool of global actuaries.

Case in point:

I recently connected, via LinkedIn, with an actuary in New Zealand. We’ve never met. You can’t physically get much further away from Ireland than New Zealand. Turns out his colleague, sitting next to him, is another actuary I started my actuarial career with in London nearly 20 years ago, and hadn’t seen since then.

Probability calculations on a postcard, please.

24

Application

A few years ago I was explaining the concept of infinity to my son. His little perplexed face said it all. I had failed miserably.

A few days later I heard him screaming from the bathroom, so I literally sprinted up the stairs.

Expecting the worst, I was confused and relieved by the sight of him sitting calmly on the floor with 2 mirrors.

He had placed them together and created an infinite reflection as each mirror repeatedly reflected the other. He had discovered infinity and his shouts were simply his excitement at letting me know.

In that instant, infinity, for my son, had moved from being an abstract concept, to something tangible and real, in his little brain. Probably locked into his neural pathways for the rest of his life.

It reminded me, how we can only learn some things in life through experience. Life and business lessons such as becoming independent, how life can be hard, moving on from failure and that nearly everything is a choice.

From an actuarial perspective, it’s why I always encourage actuarial students to relate the theory to real life. It’s why I prefer to teach actuaries through practical doing. It’s why I love the actuarial profession (solving real business and societal problems).

In theory, reality and theory are the same, in reality they aren’t.

25

Actuarial Generalist Vs Actuarial Specialist

Actuaries often work in quite specialised areas (generating dots), but as technology and automation increasingly replace roles, perhaps there’s an argument towards the generalist (the dot connector) being able to adapt better to change?

What are the actuarial career implications of going down both actuarial career paths?

Is there an optimal middle road?

Should our time be spent perfecting and improving our current skills or learning new ones?

Are specialists at risk of future actuarial career extinction?

Does being a specialist restrict our way of thinking or does the specialised knowledge and thinking create barriers of career protection?

On a related note I love this quote from Robert A Heinlein in favour of being a generalist in life!…

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”

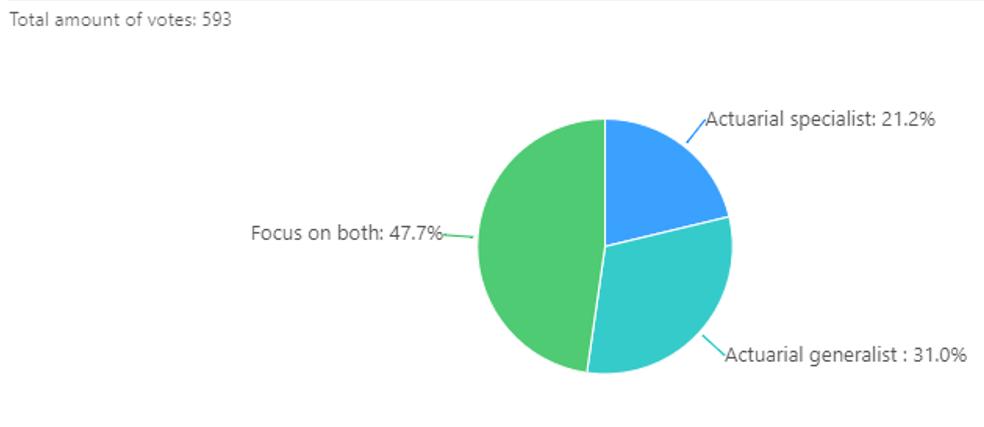

To delve into this further, I asked my actuarial contacts: “Should future actuaries focus on becoming actuarial generalists, actuarial specialists, or both in their actuarial career?”

593 people voted and the final poll results are shown below.

Original poll and discussion: https://lnkd.in/eD_T8e8

A few related quotes to ponder…

“Equipped with knives all over, yet none is sharp” – Chinese Saying

“The future belongs to the integrators.” – Educator Ernest Boyer

“Jack of all trades, master of none.” – English Saying

“It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive but those who can best manage change.” – Charles Darwin

“Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses — especially learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.” – Leonardo Da Vinci

“You have to be odd to be number 1.” – Dr. Seuss

26

Perception

You know you are an actuary when…

- You view the cost of a pint of beer not as £5.40 but instead as giving up £5.40*(1+i)^(NRA-age) in retirement

- You automatically scenario test everything that can go wrong when going on holiday

- You mentally calculate the probability of a car hitting you when you go on a road cycling ride

- You intuitively calculate a posterior probability when you realise how many crazy drivers are out there

- You picture the tail end of a bell curve when you meet someone 6 ft 8″ tall

- You laugh out loud when you witness someone convinced that red has to come up on a roulette table because the last 7 spins came up red

- You shake your head in disbelief at someone playing a slot machine thousands of times with an expectation of an end profit

- You hear an economic forecast and immediately think of it with a confidence interval

- You roll your eyes when you see someone view a “statistically significant result” as definitive proof of something

- You worry more about dying via a lightning strike than by an air crash (ie very little)

- You win a free ticket to a big concert, but you still view the (opportunity) cost of going as £300 because that’s what you could have sold it for in the open market

Or is this just me?

27

Rest

A running actuarial joke is that an actuary is a computer with a heart.

There’s probably some truth to it.

My own current “computer trait” is that of having a mental “shut down complete” switch at the end of the day (idea borrowed from Cal Newport).

Over the years I have found the boundaries between work and home life to become increasingly blurred as technology allows us to work from anywhere and WFH is more prevalent in the post-covid world.

It’s too easy to work longer hours, to flip open the laptop/smartphone and allow work to permeate into evening/weekend home life.

I enjoy my work, but I’ve realised I prefer to keep it separate from home life.

So I’ve been experimenting with book-ending some days with a “shut down complete” ritual.

I’ve heard it referred to as a digital sunset. I like that phrase. 5pm. Computer shut down. Smart phone off. Work over. Mental shut down. Family time.

28

Belief Systems

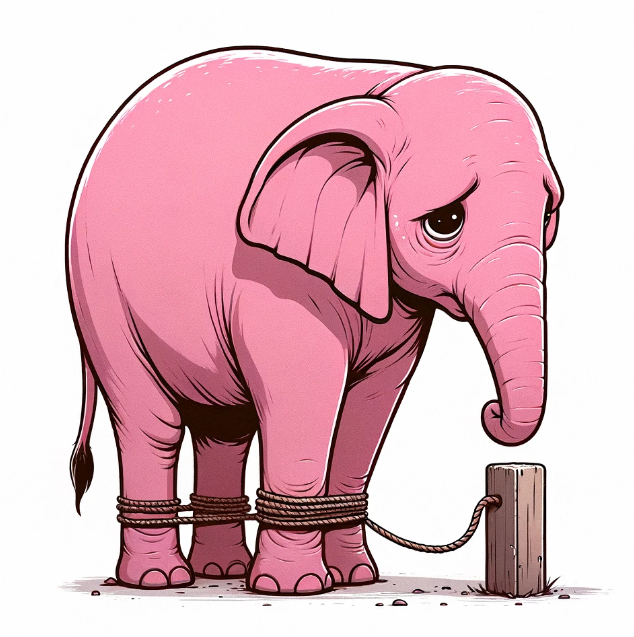

I sometimes hear my psychologist wife talk about “learned helplessness”. I believe it’s a very real phenomenon. Like a grown elephant that learnt as a baby elephant it couldn’t break free from being tied to a stake in the ground, and as a grown elephant no longer even tries, our own internal belief system can imprison us.

A good practice is, therefore, to deeply question our assumptions about what we can and can’t do. To challenge our belief systems.

In 2020 I organised our first virtual summit for actuaries – The Digital Actuary. No team. No big resources. Just an idea to bring some great people together, to help move the actuarial profession forward, and a willingness to make it happen. 4,257 people from across the world registered.

In a world of virtual clicks and likes, it’s easy to lose perspective of that number. But when I imagine 4,257 people in a conference venue that number seems surreal. Something I would never have imagined creating by myself a few years ago. My belief then would have been that it wasn’t possible.

I’m proud of the 22 speakers that freely gave their advice and time.

I’m proud of the 4,257 attendees that invested in themselves.

But most of all, I’m proud of the fact that I pulled one of my own stakes out of the ground.

29

Assumptions

As problem solvers and model builders, I believe our actuarial career should involve always questioning the assumptions upon which a problem is based.

This short humorous story from ‘Smartcuts,’ by Shane Snow, is a good example of lateral thinking:

Pretend you are in a car in the middle of a thunderstorm and you happen upon three people on the side of the road. One of them is a frail old woman, who looks on the verge of collapse. Another is a friend who once saved your life. The other is the romantic interest of your dreams, and this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to meet him or her. You have only one other seat in the car. Who do you pick up? There’s a good reason to choose any of the three. The old woman needs help. The friend deserves your payback. And clearly, a happy future with the man or woman of your dreams will have an enormous long-term impact on your life. So, who should you pick? The old woman, of course. Then, give the car keys to your friend, and stay behind with the romantic interest to wait for the bus!”

30

Authenticity

“Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken.”

— Oscar Wilde

The nature and role of the workplace appears to be changing. The internet and social media in general seems to have brought about more authenticity in the corporate space, at the individual level.

People on Zoom, LinkedIn etc seem more willing to let their professional corporate guard down. To reveal more about their personality and their struggles. To let people into their personal lives a bit more.

There appears to be more hunger for genuine interactions, honesty and transparency. Watching this unravel over the years, it almost feels like a subtle, but significant, value system change in employees, business owners and leaders in the business world.

For example, I recently saw the IFoA’s past president, John Taylor open up, in a blog post, about his own personal mental health struggles.

I’d admired the work of the IFoA past president during his presidency, but my view of him shifted after that ‘reveal.’ In an instant he became more than someone helping to lead our profession. In my mind he is now also someone that has immense bravery. Someone with a sincere willingness to take a personal reputational risk, to help others (which I believe it did). A genuine leader. I wonder how many other people feel the same.

Imho the increased authenticity is a good thing.

“I’d rather be hated for who I am than loved for who I am not.”

— Kurt Cobain

31

Embrace Change

2005 Actuarial Graduate wants:

- A high starting salary

- Bonus and salary progression potential

- A good supportive study package

- Actuarial career satisfaction

- Job security

2015 Actuarial Graduate wants:

- All the above +

- Opportunity for travel

- Some flexibility (eg a day to work/study from home each week)

- Training and personal development

2025 Actuarial Graduate wants:

- Most of the above +

- Exposure to cutting-edge tools and technology

- The chance to work on exciting projects (eg with new emerging data)

- Greater flexibility and control over where they work, when they work, what they work on, who they work with and how much they work

- Opportunities to develop as both a specialist and a generalist

- Time and support to keep learning and developing in a meaningful value additive way (not just ticking a CPD/personal development box)

- To make a difference

- Balance – time (and permission) for family and for looking after oneself

- Opportunities to apply creativity and develop curiosity

- Better control over assessment metrics

32

Move

I’ve been researching wearable usage in insurance for a while now. In the process I’ve trialled many different wearable devices. From a continuous blood glucose monitor to heart monitors to my amazing high-tech Oura ring with its multitude of sensors.

However, my current favourite wearable is a very cheap (ugly?) basic Casio watch. Why? Because it has a very important feature. A count down timer that gently vibrates when the time hits zero.

Every time I sit down to work I set the timer for 30 minutes. When the timer vibrates, I get up from my work desk, regardless of what I’m doing, and do something else. A few minutes playing with my kids, a quick walk, get some water, some brief exercise. Anything really that involves some exercise and breaks the “sitting all day” pattern.

Excessive sitting has been linked to everything from increased risk of obesity and depression to heart disease. I also find excessive sitting, without adequate breaks, makes me feel icky at the end of the day.

Natural health and fitness is much more about frequent activities and not simply doing a 1 hour gym session, after sitting all day. As much as I enjoy working at a computer, we were born to move and not sit at a desk all day long.

33

Question Everything

Question everything is a mantra that has served me well for the last 22+ years.

True story about what led to me embedding this message into my psyche:

In 1999 I was backpacking in Asia and became friends with a Chilean chap who went off to India. I received an email a month later telling me he had done a (10 day) silent meditation retreat and there was one in Thailand I should rise to the challenge of doing.

So I jumped on a bus to a remote monastery, deep in rural Thailand. For 10 long days a loud gong awakened me at 5am to meditate in silence throughout the day, before going to bed and getting up to do it all again.

10 days. No speaking. Just silence and meditation. Hour after hour. Day after day. I spent much of my meditation time in a small jail like chamber. I didn’t dare lie down in case one of the monks peered in. It was one of the most difficult things I have ever done (actuarial study = easy in comparison!).

Finally, day 10 arrived and I was free to leave (and speak again).

I emailed my friend to claim equal standing.

His reply: “You seriously done 10 days? I gave up after day 2!”

Question everything you read or hear in life. There are often blatant lies, half truths, wrong assumptions and an infinite # of perceptions if we look hard enough.

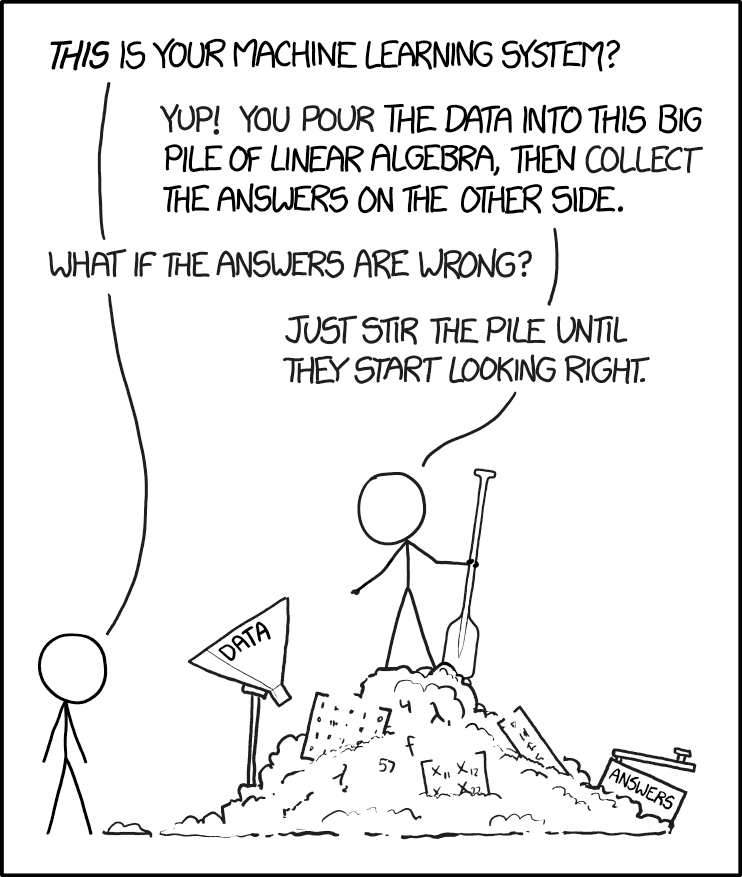

This humorous graphic reminds me why I still practice this today. Especially now, as we are being bombarded daily with new (often contradictory) models.

With every model I see, I ask myself questions such as:

Source: https://xkcd.com/1838/

Have the authors..

- A vested interest?

- Significant credibility?

- Confused causation with correlation?

- Succumbed to bias?

- Discarded unfavourable data without good reason?

- Overgeneralised (to the population as a whole) based on a biased sample?

- Found a random result or, worse, p-hacked the data to death (eg running many regressions/testing numerous hypotheses on a dataset, until they eventually find a suitable p-value and then reporting statistical significance)?

- Failed to be transparent (eg not disclosing important limitations, inputs, methodologies and model assumptions)?

I think it’s good to be skeptical and question everything. Trusting blindly can be one of the biggest risks of all.

But also don’t automatically discount models which aren’t perfect and have limitations.

Remember that science is usually a slow progression eventually converging towards less uncertainty.

34

Prediction Is an Unpredictable Business

In times of future uncertainty we are naturally, and quite rightly, drawn to the experts that help us predict what might happen. The scientists, the actuaries, the data scientists, the statisticians, the economists etc.

But let’s not forget that predicting the future is not an exact science. We are all constrained by our own unique (and very limited) experiences, mental models and knowledge.

Remember..

- Einstein once claimed ”there is not the slightest indication that nuclear energy will ever be obtainable.”

- Bill Gates used to think that no one would ever need more than 640K of memory.

- Edison told us “The radio craze will die out in time.”

- In the peak before the 1929 market crash, economist and Yale professor Irving Fisher said “what looks like a permanently high plateau… I believe the principle of the investment trusts is sound, and the public is justified in participating in them.”

- The father of AI, Herbert Simon, warned us in 1956 that “Machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.”

The future has a way of arriving unannounced.” — George Will

“The future has a way of arriving unannounced.”

— George Will

35

Create a Bright Line Actuarial Contract

Actuarial students, studying for actuarial exams, should have a non-negotiable ‘bright-line’ contract with themselves.

Not a fuzzy contract, but a clearly defined rule or standard which leaves little or no room for varying interpretation. Lawyers refer to these as bright line rules. The purpose of a bright-line rule is to produce predictable and consistent results in its application.

“I will study more” — not so bright.

“I will study CS2 every morning, Mon-Fri, 7-8 am before I start work” — passes the bright line test!

Hence it’s clear when you have broken the standard you have set for yourself.

From my experience (for general habit formation, not just study habits) vague and fuzzy doesn’t work, but clear unambiguous ‘bright-line’ commitments do.

If you want to expedite your actuarial career, create bright line contracts with yourself.

36

Actuarial Models

All models are wrong, but some are useful” — George E.P. Box

“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

— George E.P. Box

Never before has George Box’s simple quote, about model building, seemed quite so important.

Models are never completely true and hence the wrong question to ask is whether it is true, but rather whether or not it is useful. Or as Box says “the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.” and “Since all models are wrong the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong. It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers aboard.”

Since models don’t replicate reality exactly, they are therefore partly art. Whilst eternal truth is generally elusive, our various ‘models of truth’ range from very useful to useless to (as we have recently witnessed) even potentially dangerous.

I like what Pablo Picasso had to say on this:

“We all know that art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.”

37

Probability Nudging

Every morning I end my morning shower with a full on 35 second blast at the coldest possible setting (not sure why I settled on 35 seconds!).

There are supposedly many health benefits of cold water immersion. But more importantly, for me, it serves as a daily reminder of one of my favourite quotes:

“The pain of regret is worse than the pain of discipline.”

Sounds corny. Like something you might hear at a Tony Robbins seminar. But I’ve found it to be a very useful idea to keep at the forefront of my mind.

Every day we are faced with many small decisions. Yes or no. Do it or don’t do it. Eat it or don’t eat it. Study or don’t study. Exercise or don’t exercise. Vent or don’t vent.

And just like money in the bank these decisions tend to compound over time.

Like most people, I make sub-optimal decisions more often than I care to admit. Taking the easy road when the harder road was the better long term choice, in terms of present value of future happiness.

However this little routine or ‘hack’ helps to nudge up the probability of making better decisions day after day.

It’s 35 seconds of my day well spent.

38

The Best Lessons Don’t Come from a Book

When I was 11 years old, I made a fortune selling chocolate bars at school.

I would buy them in bulk in Woolworths every morning for about 14p per bar. I then sold them for 25p and on an average day I sold 50. £5 was great money back in 1989.

But then new entrants came into the market, as my classmates noticed my wealth.

I had to create a barrier to entry and a unique USP.

Barrier: The optimal selling time was straight after morning assembly before the headmaster and other teachers came out. The volume of student traffic was high. But selling goods was banned, so no one dared risk selling at this time, for fear of getting caught. Except for me. Within that 5-10 minute window, I typically sold my full day’s goods. £5 in 5 minutes (equivalent to £60/hr or £150/hr in today’s money). Not bad for an 11-year-old. It was my first introduction to risk premium.

USP: I decided to offer credit. It worked well, but chasing and writing off bad debts became new knowledge for me. It was my first introduction to cash flow and risk.

It’s funny how I remember more from lessons like these (sales, profit margin, barriers to entry, supply/demand, negotiation, USPs, risk premiums, market saturation, profit and loss, cash flow management and bad debts etc.) than I do from lessons in the classroom.

39

Questions

Any actuaries or risk managers involved in a qualitative post-mortem risk analysis, would do well to remember the 1974 study carried at the University of California by psychologists Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer.

The researchers showed just how deceiving our memories can be by asking participants to watch a car crash on TV and then questioning them as if they were eyewitnesses to the crash.

After watching the car crash, the groups were asked “how fast were the cars going when they ——– each other?”.

They used different verbs as part of the questioning process, which drastically changed how the groups recalled the event. One group had the word “smashed” used in the Q and the other group, used the word “hit“.

A week later, the participants were asked if they had seen glass at the car crash scene (this Q was asked amongst other Qs).

Those that had been questioned using the verb “smash” were much more likely to report seeing glass than those originally questioned using the word “hit”.

Be careful how you ask questions, as memories are easily distorted and manipulated!

40

Beware of Hedonic Adaptation

I grew up in a Northern Ireland border town amidst the so called “troubles”, often referred to as a “low level war”.

Childhood life was, in some ways, unusual.

If you’ve seen the Oscar winning movie Belfast, you’ll have an idea what things were sometimes like.

Some childhood memories include:

- soldiers patrolling the streets & regularly coming on to our school bus checking for bombs.

- a bomb going off, on a Sunday morning, in the exact spot I disembarked daily from my school bus (tragically killing 12 innocent people).

- my mother frantically pushing my sister, a new-born baby, in a pushchair through a crowded shopping centre when a bomb scare was alarmed.

- almost daily news of senseless killings & tit for tat murders.

These were, at the time, ‘normal’ occurrences.

Looking back now, the strange thing is, we didn’t live in fear.

Most people just kind of got on with life going to cinemas, shops & pubs even though there was always the risk of a bomb or shooting.

It seemed that people normalised things & “carried on as normal.”

The concept of “normalisation” is worth thinking about.

The idea that humans tend to return to some sort of baseline happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes.

Psychologists have a fancy term for it—hedonic adaptation.

It goes in both directions—goals & “success” in life often bring only fleeting jumps in utility, as we eventually revert back towards our mean happiness level.

Surely, therefore, we should all keep this forefront in mind when we set & pursue goals in life?

Before leaning the ladder against the wall, doesn’t it make sense to truly examine the wall & question how much extra ‘happiness’ it will bring?

Every year I give a number of talks to students interested in a possible career as an actuary.

Occasionally someone asks, “How much money do actuaries get paid?”

My next question is always, “Who is here because you’ve read somewhere actuaries get paid lots of money?”

A few sheepish (or brazen) souls usually raise their hand.

At this point I remember hedonic adaptation & highlight why I think it’s a dangerous game to enter the profession motivated mainly by money. Side note: If money is your main motivation, there are easier ways to achieve your objective.

The world often tells us to strive, push & achieve.

But it’s important to realise, every goal has a price.

If you are going to pay a hefty fare, it makes sense to closely examine the upside, allow for hedonic adaptation & make sure it is worth the tag.

Sometimes learning to want what you already have is a better strategy than getting more.

—————————————————————————————————————————————

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this and picked up a few thoughts for helping with your future actuarial career. I plan to add more content to this post in the future. Thanks for reading!

TO BE CONTINUED….