ERM Actuary: Mastering Risk Management with Expertise

Are you a graduate actuary, a part-qualified actuary, a newly qualified actuary or even a more senior qualified actuary looking to take your understanding of risk management to the next level? Or maybe you are an actuary studying ST9 for CERA. Maybe a career as an ERM actuary is waiting for you. If you are an actuary that wants to know more about the world of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) read on.

Imagine being able to anticipate potential threats to your organization before they happen and having a plan in place to mitigate them. Enterprise risk management (ERM) is the key to achieving this level of risk intelligence. As an actuary, you have a unique skillset that makes you well-suited to lead an ERM program.

This in-depth guide to ERM, written specifically with actuaries in mind will help you to understand the concepts of ERM.

The importance of ERM cannot be overstated in today’s fast-paced and ever-changing business environment, and this article serves as a valuable resource for actuaries seeking to deepen their understanding of this vital subject.

The Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Actuary

What is the ERM actuary? Why is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) important for you as an actuary?

To answer these questions we first need to take a step back and think about what exactly risk is:

Risk & Reward

Defining risk and deciding how to manage it are key considerations for modern corporate management.

Risk is a nebulous concept, with no single accepted view or definition. Different fields may view risk in often seemingly disparate ways. For example, numerically focused professionals, such as actuaries, view risk as an objective phenomenon which is quantifiable.

In the world of finance, risk is often viewed as the chance that the return achieved on an investment will differ from that which is expected. In other words, volatility of return. Social sciences take a contrasting perspective, envisaging risk as a subjective phenomenon which is not always accurately quantifiable.

Despite these discrepancies in defining risk, it is widely accepted that the pursuit of greater returns requires additional risk exposure by the enterprise. The greater the risk exposure, the greater the potential reward on offer. Or in layman’s terms, “there is no such thing as a free lunch.” From a corporate perspective, shareholders invest funds in the organisation and expect to receive a return commensurate with the level of risk they perceive they are undertaking.

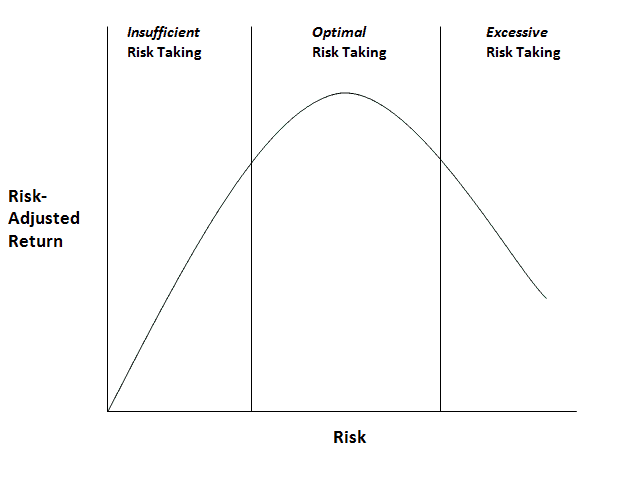

Deciding upon the appropriate level of risk to undertake is therefore a key corporate consideration, which the ERM actuary will need to carefully consider. It is often a delicate balancing act with a fine margin for error. If the enterprise does not take on enough risk, they may err on the side of over-cautious risk aversion and may not be fully exploiting potential investment projects.

On the opposing side of the continuum, excessive risk-taking can leave the organisation in a precarious position, whereby their level of risk exposure is higher than the absorption capabilities of their provisioned capital (i.e., the amount of liquid cash the organisation needs to hold to safeguard its solvency and economic stability regarding the investment project(s) in question).

The optimal risk-taking position lies between these extremes and is characterised by exposing the organisation to an acceptable level of risk that also enhances the potential investment return.

The Risk/Return Profile

The above diagram highlights this delicate and important relationship between optimal risk and return by showing how the optimal risk-adjusted return is found by striking an appropriate balance between low-risk exposure and aggressive risk-taking.

From a corporate finance viewpoint, the additional risk can come in the form of systematic risk, which relates to undiversifiable market uncertainties, or from firm-specific idiosyncratic risk.

From a portfolio perspective, risk that cannot be eliminated, via diversification, requires an enhanced expected return, above the risk-free rate, for an investor to be motivated to undertake it.

The firm-specific (idiosyncratic) risk and the treatment of it, within an appropriate risk management framework, is a widely debated topic.

Early research by Modigliani and Miller (1958) questions the validity of risk management efforts. However, more recent risk practitioners and scholars, such as ERM actuary and author of “Financial Enterprise Risk Management,” Paul Sweeting, have outlined the benefits and rationale for managing risk, such that nearly all organisations now engage in risk management to some extent.

With this increased acceptance of risk management as a potentially valuable and even necessary business activity, the discipline itself has naturally evolved. A prominent development has been the movement towards managing risks in a more integrated enterprise-wide fashion that considers risk in a portfolio context (although Markowitz developed his efficient frontier theory primarily for portfolio asset management, it revolutionised how risk was managed in every industry and also draws parallels to the ERM approach) and inherently aligns risk management with corporate governance and strategy.

This emerging holistic approach to the aggregation of risk is generally referred to as Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). The actuarial profession has also embraced the idea of the ERM actuary, over the last two decades, with many actuaries taking on positions such as the Chief Risk Officer (CRO), where they are tasked with overseeing the holistic aggregated risk position of the enterprise.

The Emergence of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)

Modern businesses have to contend with increasing complexities due to the rapid and dynamic change and ever-growing volume of global interconnections. Consider, for example, the effect increasing computing power and internet technology has had on how businesses market, sell and operate.

This pace of change shows no sign of slowing down as emerging technologies, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence, now coming to the fore.

ERM is a multifaceted, ambiguous concept that eludes simple interpretation. The integration of risk management techniques into a holistic and integrated framework is defined by COSO (2004) who define ERM as:

Enterprise risk management is a process, effected by an entity’s board of directors, management and other personnel, applied in strategy setting and across the enterprise, designed to identify potential events that may affect the entity, and manage risk to be within its risk appetite, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of entity objectives.

From the firm-specific perspective, it is evident that risk management has seen some catastrophic failures over the last 25 years. The infamous Barings Bank collapse in 1995 represented the failure of risk management systems to monitor, detect and limit the actions of a rogue trader who had concentrated risks in increasingly larger amounts to conceal trading losses.

The Enron (2001) and Worldcom (2002) debacles had, at their core, a breakdown in corporate reporting systems that masked underlying risk exposures. The collapse of Lehman Brothers (2008), perhaps the most enduring event of the most recent financial crisis resulted from an explosion in underwriting activity in subprime mortgage related products combined with an arguable lack of understanding of risk exposures at the upper echelons.

In particular, underestimation of underlying asset correlations and the risks posed by these products led to an inherent vulnerability of the institution, which ultimately toppled in the systemic downturn of 2007-2008. More recently, in 2020, we have witnessed worldwide businesses struggling to maintain operations because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Arguably, many of these failures can be attributed to the piece-meal approach that has arisen from traditional, silo-based risk management processes. Up until the mid-1990s, a silo approach to corporate risk management was habitually used, (often termed Traditional Risk Management (TRM)). This approach is characterised by the management of individual risks in separate units often using a highly disaggregated method.

In contrast, the discipline of ERM takes the advanced view that risk management needs to bring together the individual silos of risk management under a more portfolio-based, holistic approach.

The aggregation of significant hazard, financial, operational and strategic risks marks a shift in focus from a defensive endeavour to a more offensive discipline. In other words, the ERM approach is a result of the maturing, continuing growth and evolution of the risk management division and its application in a more structured and disciplined way (McCarthy and Flynn, 2004).

By breaking down the historical silos, operating within the organisation, and tackling risk on an enterprise-wide scale, in an aggregated enterprise-wide fashion, the risk management process is equipped to deal with the additional threats and opportunities faced in the rapidly evolving business world.

As the world has changed at a rapid rate over the last two decades so has the role that risk management plays within the organisation. An increasingly complex layer of connected risks has called for the adoption of an integrated, holistic approach to risk management. Actuarial and corporate risk management strategies have expanded beyond financial and hazard risk mitigation practices, such as using insurance and financial hedging instruments, to now include a multitude of other risk types, such as operational risk, reputational risk and strategic risk.

Risk management is no longer confined within the traditional silos of operation that existed in the past. Whereas historically, risk management activities were compartmentalised and uncoordinated with a focus on using insurance and derivative instruments to protect the firm against hazard and financial risks, a holistic approach has emerged to coordinate management of all significant risk exposures the organisation faces (McShane et al., 2011).

D’Arcy and Brogan (2001) put forward the following alternative ERM definition, adopted from the Casualty Actuarial Society (CAS):

ERM is the process by which organisations in all industries assess, control, exploit, finance and monitor risks from all sources for the purpose of increasing the organisation’s short and long-term value to its stakeholders.

This definition is particularly revealing as it highlights some key ERM principles and important differentiators from more traditional risk management practices:

- ERM is a discipline and should therefore have support from the top of the organisation to be carried out in an orderly, prescribed manner.

- ERM applies to all industries, not just the financial industry.

- ERM focuses on all risk types, not just those that are insurable or financial in nature.

- ERM accounts for all stakeholders, not just shareholders. Hence regulators, customers, employees and suppliers may all be considered in the ERM process.

- ERM is focused on the long-term and should ultimately create tangible value for the organisation.

Embracing ERM from a management perspective may seem intuitively obvious and enticing, especially in turbulent times, when one considers the potential ERM benefits, such as:

- Helping choose the optimal level of risk for the organisation (Meulbroek, 2002).

- Improving internal project decision making (Nocco and Stulz, 2006)

- Enhancing capital efficiency (Myers and Read, 2001).

- Reducing hedging and insurance risk management expenditures through recognition of diversification effects (KPMG, 2009).

- Improving board transparency (Beasley et al, 2005).

- Reducing capital costs (Samanta et al, 2004).

- Reducing the volatility of returns (Sweeting, 2011).

However, the ERM actuary must consider whether the potential paybacks from ERM when weighed against the absorption of finance and human resources (which may be material for such an enterprise-wide undertaking) are worthwhile.

Despite the theoretical rationales listed above, if and to what extent ERM adds value has yet to be established with a high degree of certainty.

Researchers, such as Beasley et al. (2008) and Hoyt and Liebenberg (2011), provided some initial evidence for ERM value creation, but a major validity impediment of these studies has been the development of a reliable measure of the ERM construct (McShane et al., 2011).

Beasley et al. (2008), Hoyt and Liebenberg (2011) and Lin et al. (2012) utilise Chief Risk Officer (CRO) appointments as a binary proxy for ERM implementation and base their findings on the supposition that CRO appointment is indicative of ERM implementation. The rationale being that the CRO is the executive accountable for enabling the efficient and effective governance of significant risks, and related opportunities, to a business and its various segments. In more complex organisations, the CRO is generally responsible for coordinating the organisation’s ERM efforts.

Clearly, the literature has fallen short on using an all-encompassing ERM measure that addresses and explores the actual processes and factors (Kraus, 2012). I, therefore, argue that much of the empirical evidence presented to date only provides early indication of a relationship between ERM and firm value. There is a need to empirically examine the ERM value relationship with a much more valid and revealing ERM construct. Additionally, researchers (Beasley et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2012) have also found early evidence to suggest that ERM does not in fact create value and may potentially destroy it.

In my widely cited 2015 paper, “The Valuation Implications of ERM Maturity” I was able to use a newly available, and previously under-utilised, data-rich source from the Risk and Insurance Society that provides in-depth ERM maturity model survey responses from a sample of public listed organisations. I used this data to empirically investigate the relationship between the extent of ERM implementation and firm performance to provide a unique contribution to the relationship between ERM maturity and firm value.

From Traditional Risk Management to Enterprise Risk Management

Risk management is often referred to as the process of identifying, assessing and prioritising risk exposures followed by a co-ordinated application of resources to effectively minimise, monitor and control the likelihood and/or severity of negative events. Over the last 70 years, businesses have increasingly taken risk management into consideration as part of operating a successful long-term company.

Risk management particularly came into effect in the 1970s and 1980s as organisations realised that firm-specific risks (also known as idiosyncratic or unsystematic risk) were important to be managed, making it a high-priority item for investors.

Prior to this time period, risk management focused on managing the downside of risk, which was typically resolved through insurance, which simply pooled the risk with other similar risks, thus allowing the insurer to accept the transfer of risk in a profitable and mutually beneficial setting. By pooling risks together, an insurance company can utilise actuarial science theory and loss distributions to predict with a high degree of accuracy the potential losses (claims) from year to year.

However, the transfer of risks via insurance only took into consideration hazard type risk exposures, which, although important, only pertain to a sub-section of risks the organisation may face. Insurable hazard risks are typically risks that are independent, measurable and do not allow the organisation to benefit (i.e. no potential upside in contrast to (for example) financial risks). Hence it became increasingly evident that some risks that were previously transferred to an insurer could instead be prevented, or their severity reduced, through efficient loss-prevention and control systems. Furthermore, it often made sense to instead retain some of these risks within the company. This led to a broader risk management approach to insurable hazard risks.

As the use of financial derivative products gained momentum in the early 1970s, risk management moved away from being a reactive process to focus more on proactive procedural practices.

Most ERM actuaries will be familiar with the work of Black and Scholes who published the ‘Option Pricing Model’ in 1973, ushering in more modern aspects of risk management where risks outside the aforementioned insurable hazard risks (e.g., financial risks) could be effectively priced and also mitigated. They found that the use of their pricing model provided a mechanism whereby organisations could effectively hedge their financial risks by openly trading derivative products on an exchange, at a price that accurately reflected their risk. These developments have led to a much more fluid and active transfer of risk between parties and have formed much of today’s corporate risk mitigation strategies.

It seems reasonable to assert that an optimal strategy for achieving success is to maximise strengths and minimise weaknesses. Bernstein (1998) applied this same line of thought to risk management by conveying: “The essence of risk management lies in maximizing the areas where we have some control over the outcome while minimizing the areas where we have absolutely no control over the outcome and linkage between effect and cause is hidden from us”. It is therefore clear that risk management plays an integral role in successfully achieving business objectives and has become a part of every organisation.

There is no one way to practise risk management, as it should be scaled according to not only the size of the organisation, but also based on the nature and complexity of the risks it faces. In other words risk management should be practised in accordance with the organisation’s risk tolerance.

Risk tolerance is a measure of the amount of uncertainty that an organisation is prepared to accept in respect of negative changes to its business or assets. This differs slightly from ‘risk appetite’, which can be defined as ‘the amount and type of risk that an organisation is willing to take in order to meet their strategic objectives. Risk management should also be comprehensive and dynamic enough to react to changes as necessary.

ERM

ERM is considered to be an advanced framework for risk management, and it first appeared in 1995 in the Joint Australia/New Zealand Standard for Risk Management (AS/NZs, 2004). However, it was James Lam who, in 1993, became the first person to use the title of “Chief Risk Officer” even before ERM became mainstream (Lam, 2014). The appointment of a CRO is often regarded as a signal of holistic risk management implementation and has therefore frequently been used as a proxy for ERM in many academic studies.

ERM is often viewed as a difficult to define discipline, but most ERM literature seems to agree that it relates to interchangeable concepts, such as “integrated risk management”, “strategic risk management” and “holistic risk management”. For instance, Beasley et al. (2006) introduce ERM as a holistic approach across an entire organisation, and McShane et al. (2011) argue that ERM is “a construct that ostensibly overcomes limitations of silo-based traditional risk management”.

Although scholars and organisations have taken differing slants on their views of ERM, we can draw some clear parallels from the various definitions. Namely, that ERM is an integrated and holistic evaluation of all the risks facing an organisation with a focus on how those risks affect the organisation in aggregate. Integration is therefore a key component of ERM and stems from:

- An integrated risk organisation that encourages a centralised risk management process.

- The integration of risk-transfer strategies.

- The integration of risk management into the firm’s culture and corporate decision making processes.

Scholarly research, such as that carried out by Banham (1999), Doherty (2000) and Meulbroek (2002) support the view that ERM is an integrated risk management framework and allows managers to benefit from new insights with regard to risk correlations and connections, which are generally missed without an all-encompassing and comprehensive approach.

This movement away from an exclusive focus on financial and insurable risks, towards encompassing the full spectrum of risks, is a key differentiator from traditional risk management approaches. A further differentiator between TRM and ERM practices is the fact that ERM does not simply attempt to minimise an organisation’s risk threat, as TRM practices may have done, but instead focuses on risk opportunities and even how risk can be actively sought for competitive advantage. This vantage point is very important for the ERM actuary, since from this new perspective, many ERM definitions stress value creation and how the implementation of the ERM discipline can help a business improve decision making, thus increasing the likelihood of achieving business objectives.

Although ERM has been recognised as a discipline for less than three decades, the debate for a holistic risk management approach has been on-going perhaps since Kloman’s (1976) publication of “The Risk Management Revolution”. Kloman (1976) advocated for a more coordinated, or “holistic”, approach to risk management, and other researchers, such as Crockford (1980), Bannister and Bawcutt (1981) and Stulz (1996), all called for a move away from the silo-based practice of TRM, towards a more optimised risk management system that integrated activities under a single framework.

With the range of risks that companies feel they need to manage continually expanding there has been an increasing recognition that most guidelines, methods and best practises focus on only a specific part of the business and do not take a systematic approach to the problems most organisations face.

ERM builds upon TRM procedures by taking a holistic approach to the measurement and management of all significant risks, hence providing an improved framework to deal with an increasing array of inter-connected risk exposures.

Kraus and Lehner (2012) discussed how two early facets of TRM practices have been incorporated into ERM. Firstly, they contest that since company risk management practices have become more sophisticated over time, managers recognise that both financial risks (such as movements in stock prices, commodity prices, exchange rates and interest rates) and non-financial risks (such as reputational, operational and strategic risks) should be managed together. This acknowledgement has led to the development of new risk-transfer products that combine more than one type of risk, such as weather derivatives and catastrophe bonds, as well as the application of copula functions to help assess risk correlations.

Again, according to Kraus and Lehner (2012), the second TRM component that has contributed to the rise of ERM relates to general management thinking. Contingency planning has always been an important part of corporate policy with the purpose of identifying activities that may be threatened by adverse events to ensure systems are in place if such events do occur. Business continuation management has extended the practice of contingency planning by requiring comprehensive internal control systems. Thus, there is evidence to suggest that TRM’s silo-based approach has been deemed inefficient as both the adverse and possibly beneficial effects of risk correlations are not adequately considered, potentially producing inefficiencies and risk oversight.

To summarise, in today’s changing business world, TRM practices are no longer viable in terms of ensuring that organisations manage risks in an enterprise-wide fashion. This has led to an advanced framework that can manage risk in a more integrated holistic fashion, such as ERM.

In the process of managing all risks, ERM must embrace every significant risk regardless of the source–whether it is strategic, financial, operational or hazard-based–to ensure that every significant risk exposure is managed in the context of the organisation as a single comprehensive entity.

The Chief Risk Officer (CRO)

The chief risk officer (CRO) plays a crucial role in the implementation and management of an organisation’s enterprise risk management (ERM) program. The CRO is responsible for leading the risk management function and ensuring that risks are identified, assessed, and mitigated in a timely and effective manner.

They also work closely with other departments, such as finance and operations, to ensure that risk management is integrated into the organisation’s overall strategy. Additionally, the CRO (or ERM actuary in insurance) is responsible for communicating the results of the ERM program to the board of directors and other senior management, as well as providing oversight to ensure that the organisation’s risk management policies and procedures are being followed.

The CRO is also responsible for the development of risk management tools and techniques, and for providing guidance to the organisation on how to handle emerging risks. Overall, the chief risk officer plays a vital role in the success of an organization’s ERM program and many actuaries are now moving into such roles.

The Certified Enterprise Risk Analyst (CERA) Qualification

The Certified Enterprise Risk Analyst (CERA) is a recent professional qualification that recognises individuals who have demonstrated advanced knowledge and expertise in ERM. The CERA credential is considered one of the premier ERM designations for actuaries and other risk management professionals.

To earn the CERA credential, candidates must pass rigorous examinations such as the ST9 Enterprise Risk Management IFoA exam, covering key areas such as:

- Governance and organisation of ERM

- Identification and assessment of risks

- Implementation and execution of risk management strategies

- Monitoring and reporting of risk management activities

Holding the CERA credential demonstrates to employers, clients, and peers that an individual has a high level of knowledge and expertise in ERM and is committed to maintaining and enhancing their skills in this area. It also provides a competitive advantage in the job market and can lead to career advancement opportunities.

The Certified Enterprise Risk Analyst (CERA) is a valuable credential for actuaries and other risk management professionals looking to demonstrate their advanced knowledge and expertise in enterprise risk management. The CERA credential is recognised globally as one of the premier ERM designations, and it can help to boost credibility, advance career opportunities, and enhance earning potential.

If you are an actuary and your goal is to become a chief risk officer then obtaining the CERA qualification may indeed make sense.

Drivers of ERM

Whilst the growth of ERM has varied by organisation and industry, the transition away from the more silo-based and less aggregated traditional risk management practices can be attributed to a number of fundamental drivers, many of which are described in detail by the Casualty Actuarial Society (CAS) ERM Committee (2003). These drivers, from the CAS, Overview of ERM paper, are summarised and discussed in turn, below.

Increasingly Complex Risks

Modern businesses are increasingly recognising the growth in both the number and nature of risks to which they are exposed. As the business landscape has altered, new vulnerabilities have grown in importance. Globalisation, for example, has led to more firms facing regulatory obstacles, geo-political exposures, supply chain risk and foreign exchange rate risk.

Furthermore, recent high-profile losses and failures, such as the 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, which has since seen BP set aside $42 billion to deal with the repercussions (Reuters, 2015), have increased focus on operational and strategic risk.

Heightened financial sophistication, advancing technology, emerging geo-political risks and accelerating business activity have also contributed to the number and the growing complexity of risks organisations face. Beasley et al. (2015a) carried out a study of more than 1,000 members of the America Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) business and industry group and found that 59% of their respondents believed that the volume and complexity of risks had changed “extensively” or “mostly” in the previous five years.

Along with increased risk levels, and increased recognition of them, ERM has also been driven by a greater awareness of the interconnected nature of risks. A study conducted by the professional services firm, Deloitte (2013), explored the extent by which risks are correlated. The study, consisting of 1,000 of the world’s largest global public companies, between 2003 and 2012, reported that 38% of companies suffered a one-month share price decline of more than 20% relative to the MSCI Global 1000 index. The study report concluded that almost 75% of these major losses occurred due to correlated and interdependent risks.

Stakeholder Pressures

Miccolis and Shah (2000) reported that both direct and indirect external pressures have driven the migration towards this integrated and strategically focused risk methodology. The 2007–2008 global financial crisis and on-going corporate risk management failures have led to a greater insistence from regulators, institutional investors and corporate governance oversight bodies that board members and senior management of organisations take more responsibility for managing risk on an enterprise-wide scale and that risk practices become much more stringent.

As an example, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) stipulates that corporations must scrutinise their risk profiles using a holistic, enterprise-wide approach as opposed to the more traditional silo-based approach. A further example highlighted by Hannoun (2010), relates to the introduction of Basel III by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in order to help correct the failings of prior accords by improving an organisation’s risk awareness and loss absorbing ability. Supporting this further, a 2008 study by Deloitte, reported that the major force behind ERM was an organisational need to respond effectively to regulation, with ERM seen as the appropriate mechanism to manage increasingly complex compliance requirements.

Rating agencies, and in particular S&P, have also begun to incorporate the presence of an ERM framework into their rating factors, and thus it can be presumed these policies serve as an additional driving factor behind ERM. Finally, it would be remiss not to mention shareholders, as the owners of public traded companies, who are exerting influence via a desire for more predictable and stable earnings if they are to invest capital. Shareholders are also increasingly seeking tangible proof of effective and value-creating risk management practices.

Portfolio Theory

A driving influence behind ERM is the management of all the significant risks facing the organisation within a portfolio context. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), developed by Markowitz in 1952, highlighted how risk-averse investors can construct investment portfolios that optimise expected investment return (based on a given level of market risk) by considering the correlation levels between the assets included in the investment portfolio. By diversifying a portfolio of financial investments (with varying levels of financial volatility risk) that were not 100% correlated, Markowitz showed that the variability in returns could be reduced.

Similarly, business entities will generally invest in a range, or portfolio, of different projects. These businesses also consist of a multitude of different departments, potentially operating from separate and often international locations. The 21st century business is increasingly exposed to a vast array of interconnected risks with varying degrees of correlation between exposures. ERM, therefore, parallels MPT by viewing the organisation’s risk exposures in a portfolio context, with inter-dependent and connected risk exposures, which can therefore be optimised by taking advantage of the “portfolio effect”.

The portfolio approach to risk management (to both financial and non-financial risks) therefore encourages a greater understanding of the total risk facing an organisation and allows senior management to diversify risks and exploit natural risk hedges (Lam, 2014). As well as the possible beneficial diversification effects of correlated risks, it should be noted that there is potential for risks to compound and lead to significant adverse effects that may not have occurred if the risks were isolated.

CAS (2003) highlights this danger by arguing: “even seemingly insignificant risks on their own have the potential, as they interact with other events and conditions, to cause great damage” (CAS, 2003).

Enhanced Risk Quantification Abilities

A further driving force in ERM adoption and consideration for ERM actuaries has been the increased ability and tendency to measure and analyse risks as a result of advances in risk-modelling expertise and technology.

Organisations are increasingly able to quantify risks, which were traditionally viewed as unpredictable or infrequent. Catastrophe modelling, for example, has been widely utilised by ERM actuaries in the insurance world since the early 1990s. Catastrophe modelling (or cat modelling) is the process of using computer-assisted calculations to estimate the losses that could be sustained due to a catastrophic event such as an earthquake or flood. These products have proven to be very popular such that in 2014, a record $8 billion worth of catastrophe bonds were issued (The Economist, 2015a).

Value-at-Risk (VaR), as a probabilistic measure of market risk, is another risk-quantification methodology that has also been widely adopted since the 1990s and now forms a large part of modern regulatory requirements, such as the Basel Accords in the banking industry. The rapidly increasing speed and ease by which technology has allowed us to measure modern financial risks has facilitated the emergence of such risk measures. This progress in risk quantification has provided regulators and organisations a level of confidence to ensure that they operate within both regulatory parameters and corporate risk-tolerance levels.

The European Union (EU) Solvency II Directive for instance, prescribes Solvency Capital Requirement for EU insurers, by specifying that they: “shall correspond to the Value-at-Risk of the basic own funds of an insurance or reinsurance undertaking subject to a confidence level of 99.5% over a one-year period” (Floreani, 2012).

The vast increase in collated data in recent years, combined with the ability for data to be instantaneously transferred, has also led to huge developments in analytical prowess. Increasingly, organisations are moving from an intuitive, ‘gut-feeling’ approach to more data-driven predictive modelling. Indeed, this movement has been witnessed across the insurance, marketing and even human resource industries.

Finally, with organisations now taking a portfolio view of risk, as described above, there is a growing effort to quantify risk correlations and the overall portfolio risk of the organisation. Whilst such quantification still remains challenging, especially in risk related areas, such as operational and strategic risk, immense value can be added to the decision making process from insights that may simply provide a direction of the risk exposure.

Benchmarking & Sharing

CAS (2003) state that: “Organisations have become quite willing to share practises and efficiency gains with others with whom they are not direct competitors” (CAS, 2003). Hence it is clear that the sharing of common tools, processes and ERM practices across industries and globally has also played a part in helping to drive and embed the ERM discipline. The internet and related technology, such as social media, has aided information sharing as well as an increased willingness among organisations to share risk practices via forums, conferences and professional bodies. This has resulted in increased transparency in terms of effective risk practices that create value and are thus worthwhile.

Focusing on the Upside of Risk

Finally, ERM adoption has been influenced by an attitude change towards risk-taking amongst business leaders of the 21st century. CAS (2003) has also recognised this by highlighting that “there is a realisation that risk is not completely avoidable and, in fact, informed risk-taking is a means to competitive advantage” (CAS, 2003). Hence the ERM actuary will seek to consider risk optimisation and not simply risk minimisation.

The world may arguably have become more uncertain, but there is evidence of this new posture towards risk taking. In the past, firms often took a defensive risk stance, simply focusing on the reduction, or even elimination, of risk via practices such as insurance. Whilst defensive risk mitigation strategies certainly play an important role in modern risk management strategies, organisations have begun to focus more on the opportunities that risk may present and how value can be created from it, by taking on risks where the organisation has a competitive advantage. A number of reasons have brought this change in attitude to the fore.

Firstly, as organisations have become more familiar with the risks to which they are exposed and have enhanced their capabilities in managing those risks over time, they have recognised their competitive advantage, such that those risk exposures have become a viable route to profit.

It is also now easier for organisations to actively seek out target risk exposures due to a more fluid market place and access to financial risk management products, such as the derivative products of forwards, futures, options and swaps. New financial products and markets also allow firms to effectively evaluate risk-return trade-offs and ensure that the benefits of certain risk strategies outweigh the costs.

Furthermore, risk may be sought out for diversification and hedging purposes in line with the desire to now view risks in a more holistic portfolio perspective. PWC (2015) surveyed over 1,000 business executives and found that the perspective of risk is changing from operational to strategic. Their study found that 31% of risk leaders are willing to accept financial risk, and 35% are willing to accept diversification and concentration of risk, both of which highlight the movement towards embracing appropriate risk-taking behaviour.

ERM & Value Creation

The theoretical value proposition of corporate risk management may seem intuitively obvious, but is however ambiguous and has historically been contested. For example, the Modigliani and Miller (1958) seminal contribution on the irrelevance of an organisation’s capital structure implies that in perfect capital markets, risk management activities also do not create value. Building on the work of Markowitz (1952), Sharpe (1964) created the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which provides the theoretically appropriate required rate of return of an asset based on the additional systematic risk it contributed to the portfolio.

When pricing the risk of adding a new asset to the portfolio, Sharpe (1964) claimed that only systematic risk should be factored in, as idiosyncratic risk can be diversified away. To this extent, an important metric used in CAPM is ‘beta’. An organisation’s beta dictates the magnitude of asset volatility in relation to market movements.

In Sharpe’s world of well-diversified portfolios, asset returns are fully determined by market fluctuations. The organisation can control their level of beta and thus manage the potency of market movements similar to the principal behind leverage. Hence, the CAPM asserts that well-diversified investors are able to hold portfolios that will have already eliminated the idiosyncratic specific risks of the firm, thus rendering risk management efforts irrelevant in terms of value creation.

However, of critical importance to the ERM actuary, there are various theoretical counter arguments that suggest risk management can and does indeed add value to the firm.

Firstly, as Grace et al. (2015) argue, the commercial environment has many market imperfections in terms of taxes (Modigliani and Miller, 1963), bankruptcy costs (Kraus and Litzenberger, 1973), external capital costs (Froot et al., 1993) and agency costs (Jensen and Meckling, 1976), which can be exploited allowing risk management to add value within the organisation. Pagach and Warr (2011) echoed this perspective by highlighting that attempts to reduce idiosyncratic risk is not a negative net present value project, due to the numerous market frictions and imperfections that exist within the corporate world.

Other arguments include recognition of the fact that well-diversified investors do not exist (Shimko, 2001) and that risk management enhances firm value by improving the value of expected cash flows (Shapiro and Titman, 1998; Nocco and Stulz, 2006). Various studies have also statistically shown that risk management appears to be adding value in the presence of these market imperfections (e.g., Smith and Stulz, 1985; MacKay and Moeller, 2007).

I now discuss the various rationales for value creation from ERM engagement, in turn below.

Optimising Risk & Return

As previously emphasised, risk management is no longer solely concerned with minimising downside risk and the ERM actuary’s focus will shift as a result.

Organisations are now challenged to view risk as an opportunity by ensuring they only take on risks where they have a competitive advantage and also by actively seeking risk exposures that may lead to valuable upsides. Reverting to the basic premise that it is not possible to yield a return without bearing some degree of uncertainty, it is clear that risk is, quite simply, an unavoidable part of doing business. Risk management practises, therefore, do not simply attempt to mitigate risk exposures, but rather, they should strive to exploit opportunities and thus optimise the risk-adjusted return through managing a degree of risk that is within a pre-determined risk tolerance.

Knight and Petty (2000) highlight this point by contesting that the development of a risk policy should be a dynamic process, which handles risks innovatively and exposes opportunities for value growth. Best practice ERM dictates that risk management processes become ingrained in a firm’s strategic planning, and therefore the ERM decision making process starts with the identification of current risk exposures as well as potential risks that could be taken, rather than acknowledging them as an afterthought or dealing with them as they arise. This approach creates a more efficient planning process that leads to a more optimal distribution of the limited capital for investment.

It is, therefore, generally recognised that ERM attempts to create shareholder value by allowing firms to achieve a more optimised risk-return trade-off. Meulbroek (2002) shares this view and argues, “The goal of risk management is not to minimize the total risk faced by a firm per se, but to choose the optimal level of risk to maximize shareholder value”. Adopting an integrated framework approach to managing risk aids in achieving this goal.

Risk Aggregation: A Holistic Approach to Risk Management

From previous discussions, it is clear that many consider fragmented risk management no longer acceptable, considering the increasingly strong intertwining connections between risks and the growing complexities of the business world. To achieve a comprehensive appraisal of all these interdependencies and manage risk in an efficient and effective manner, a holistic approach is required. The problems and frailties that surround the silo-based approach have served as a significant driving force in the expansion and development of ERM.

Hence a key aspect of ERM (and difference from the TRM approach) relevant to the ERM actuary, is that the firm’s major risks, from all sources, are aggregated together in a ‘portfolio’ of risks. Rosenberg and Schuermann (2006), for example, use a copula-based method to show that a firm’s total amount of risk differs from the sum of the enterprise’s individual risks. Nocco and Stulz (2006) contend that an evaluation of risk and return at the project level does not allow for optimisation at the corporate level, as risk diversification and correlations are ignored, thus leading to sub-optimal decision making.

As a key component of ERM is the examination of the risk interactions and their aggregation, it is therefore posited that ERM improves internal decision making and hence ultimately contributes to firm value through more efficient capital allocation (Myers and Read, 2001).

Furthermore Nocco and Stulz (2006) argue that ERM can lead to a reduction in the probability of large detrimental cash flow shortfalls (which are economically burdensome to the firm in terms of future growth implications), costly capital acquisition and relinquishing of profitable investments. In support of the argument for a holistic risk management approach, McShane et al. (2011) emphasised the benefits of ERM, attesting that hedging residual risk (rather than independent risks) maximises value by allowing the organisation to benefit from a risk diversification effect or recognition of natural risk hedges.

Thus, only the remaining risk needs to be addressed, which should be less onerous than mitigating each risk independently. Markowitz (1952) recognised that an investor can reduce portfolio risk simply by holding combinations of instruments, which are not perfectly positively correlated. As such, ERM assumes that risks are not 100% correlated. Hoyt and Liebenberg (2011) also recognise this key benefit in their discussion of how the integration of risks helps firms avoid duplication of risk management outlay.

Improved Board Decision Making

In addition, viewing the company’s risks as a portfolio should be beneficial to the firm, as it should improve both the senior management and the board’s ability to understand and oversee the enterprise’s overall level of risk exposure (Beasley et al., 2005).

This increased need for the board to truly understand the organisation’s risk position has been particularly prevalent since the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, when many commentators blamed the over-use of complex financial models and derivative products for an unhealthy gap between risks undertaken and the board’s understanding of those risks. For example, in 2008, the American International Group (AIG) received a bailout of US$85 billion primarily as a result of its misuse of financial tools known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). It is clear that the board of AIG did not have a full comprehension of the true AIG risk exposure resulting from their CDO endeavours.

Stakeholders, in the pursuit of maximising their wealth for a given level of risk, have strong incentives to ensure that the board provides effective risk oversight by practising risk management in a value-additive and transparent manner. Accurately plotting the organisation’s position on the risk/return curve requires knowledge of risk exposures on an enterprise-wide scale. An improvement in the understanding and transparency of the firm’s aggregate level of risk, right up to the board level, should allow for an efficient level of strategic decision making in line with an optimal risk-taking strategy (Chapman, 2011). Hoyt and Liebenberg (2011) posit that this improved understanding, at board level, enhances resource allocation, capital efficiency and equity return.

The ERM Actuary: Focused on Creating a Competitive Advantage

It should also be noted that ERM goes beyond focusing on just risk avoidance activities to also recognise the value of embracing risks that provide a strategic competitive advantage. This is partly in recognition of the fact that the desire for risk avoidance may actually increase the volatility and fragility of financial markets as a whole via certain investment products (Jacobs, 2004).

Key considerations and imperatives under the ERM framework include a focus on the organisation’s ability to respond appropriately, via redeployment of resources, in the face of changing business environments. This more offensive approach towards agility, pro-active risk seeking and attempting to optimise risks, rather than simply reducing or mitigating them, enables a more favourable risk profile to be achieved; such that new business opportunities can be effectively developed and executed as the competitive landscape alters (e.g., from technological innovations).

Other Noted Benefits

Other value additive benefits of ERM include reduced cost of capital via improved ratings from credit rating agencies (Samanta et al., 2004; Hoyt and Liebenberg, 2011), improved insights into different types of risk (Meulbroek, 2002), enhanced capacity to inform outsiders such as regulators and investors of the firm’s risk profile (Hoyt and Liebenberg (2011), better capital structure decision making (Graham and Rogers, 2002) and the avoidance of large swings in the staff required (thus limiting recruitment and redundancy costs), which helps reduce the amount of necessary risk capital (Sweeting, 2011).

Finally, various ERM consulting practices have also reported that ERM has led to more accurate financial reporting, an improved perception of the organisation from a plethora of stakeholders, a better marketplace presence and, in the case of public service organisations, enhanced political and community support.

The ERM Actuary: Summary

In summary, it is clear that the practice of risk management is in the midst of a paradigm shift, as the global commercial business landscape continues to rapidly evolve. ERM is a maturing discipline that aims to help organisations proactively and effectively deal with ever-changing risk exposures and resulting strategic planning requirements. The evidence is compelling that the implementation of ERM has the potential to create tangible value amongst organisations in general, but particularly amongst those that are more complex in nature or operate in a strong knowledge-based stakeholder focused environment.

The manner in which organisations manage risk has evolved significantly over the last two decades and the holistic integrated approach, known as Enterprise Risk Management, has gained significant traction throughout the corporate world.

Firms that advance ERM from a value-based perspective and focus on embedding risk culture across the organisation, encourage employees to take a more risk aware approach and align ERM with their strategic goals are realising significant value, particularly in the long-term.

As the world increases in complexity and inter-related systems require greater levels of understanding and clear communication, the ERM actuary is likely to be in strong demand.

ERM Actuary FAQs

References

Aabo, T., Fraser, J.R.S. & Simkins, B.J., 2005. The Rise and Evolution of the Chief Risk Officer: Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 17(3), pp.62–75.

Banham, R., 1999. Kit and Caboodle: Understanding The Skepticism about Enterprise Risk Management. CFO Magazine.

Bannister, J.E. & Bawcutt, P.A., 1981. Practical Risk Management, Witherby.

Beasley, M., Branson, B. & Pagach, D., 2015. An Analysis of the Maturity and Strategic Impact of Investments in ERM. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(3), pp.219–243.

Beasley, M., Branson, B., & Hancock, B., 2015a. 2015 Report on the Current State of Enterprise Risk Oversight: Update of Trend and Opportunities. ERM Initiative at North Carolina State University.

Beasley, M., Branson, B., & Hancock, B., 2015c. Global State of Enterprise Risk Management Oversight: Analysis of the Challanges and Opportunities for Improvement. ERM Initiative at North Carolina State University.

Beasley, M., Branson, B. & Hancock, B., 2010. Report on the Current State of Enterprise Risk Oversight. The ERM Initiative at North Carolina State University. Available at: http://riskwide.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ERM-Research-Study-2014.pdf.Beasley, M. et al., 2006. Working Hand in Hand: Balanced Scorecards and Enterprise Risk Management. Strategic Finance, 87(9), p.49.

Beasley, M., Pagach, D. & Warr, R., 2008. Information Conveyed in Hiring Announcements of Senior Executives Overseeing Enterprise-Wide Risk Management Processes. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 23(3), pp.311–332.

Beasley, M.S., Clune, R. & Hermanson, D.R., 2005. Enterprise Risk Management: An Empirical Analysis of Factors Associated with the Extent of Implementation. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 24(6), pp.521–531.

Bernstein, P.L., 1998. Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk. John Wiley & Sons Inc, United States of America.

Black, F. & Scholes, M., 1973. The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities. The Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), pp.637–654.

Chapman, R.J., 2011. Simple Tools and Techniques for Enterprise Risk Management, John Wiley & Sons.

Casualty Actuarial Society 2003, Overview of Enterprise Risk Management. Casualty Actuarial Society.

Crockford, N., 1980. An Introduction to Risk Management, Woodhead-Faulkner.

D’Arcy, S.P. & Brogan, J.C., 2001. Enterprise Risk Management. Journal of Risk Management of Korea, 12(1), pp.207–228.

Deloitte, 2013. The Value Killers Revisited – A Risk Management Study.

Doherty, N., 2000. Integrated Risk Management: Techniques and Strategies for Managing Corporate Risk, McGraw Hill Professional.

Farrell, M. & Gallagher, R., 2015. The Valuation Implications of Enterprise Risk Management Maturity. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 82(3), pp.625–657.

Floreani, A., 2012. Risk Measures and Capital Requirements: A Critique of the Solvency II Approach. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice, 38(2), pp.189–212.

Froot, K.A., Scharfstein, D.S. & Stein, J.C., 1993. Risk Management: Coordinating Corporate Investment and Financing Policies. The Journal of Finance, 48(5), pp.1629–1658.

Grace, M.F. et al., 2015. The Value of Investing in Enterprise Risk Management. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 82(2), pp.289–316.

Graham, J.R. & Rogers, D.A., 2002. Do Firms Hedge in Response to Tax Incentives? The Journal of Finance, 57(2), pp.815–839.

Hannoun, H., 2010. The Basel III Capital Framework: A Decisive Breakthrough. BIS, Hong Kong. Available at: https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp101125a.pdf.

Hoyt, R.E. & Liebenberg, A.P., 2011. The Value of Enterprise Risk Management. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 78(4), pp.795–822.

Jensen, M.C. & Meckling, W.H., 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), pp.305–360.

Kloman, H.F., 1976. The Risk Management Revolution. Fortune Magazine (July).

Knight, R. & Pretty, D., 2000. Philosophies of Risk, Shareholder Value and the CEO. Financial Times, 27.

Kraus, A. & Litzenberger, R.H., 1973. A State-Preference Model of Optimal Financial Leverage. The Journal of Finance, 28(4), pp.911–922.

Kraus, V. & Lehner, O.M., 2012. The Nexus of Enterprise Risk Management and Value Creation: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives, 1(1), pp.91–163.

Lam, J., 2014. Enterprise Risk Management: From Incentives to Controls. John Wiley & Sons.

Lam, J., 2011. The Role of the Board in Enterprise Risk Management-The Board of Directors has Direct Responsibility for and Significant Leverage in Ensuring that Sound Risk Management is in Place. RMA Journal, 93(7), p.51.

Lam, J., 2001. The CRO is Here to Stay. Risk Management: An International Journal, 48(4), p.16.

Lin, Y., Wen, M.-M. & Yu, J., 2012. Enterprise Risk Management: Strategic Antecedents, Risk Integration, and Performance. North American Actuarial Journal: NAAJ, 16(1), pp.1–28.

Mackay, P. & Moeller, S.B., 2007. The Value of Corporate Risk Management. The Journal of Finance, 62(3), pp.1379–1419.

Markowitz, H., 1952. Portfolio Selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), pp.77–91.

McShane, M.K., Nair, A. & Rustambekov, E., 2011. Does Enterprise Risk Management Increase Firm Value? Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 26(4), pp.641–658.

Meulbroek, L.K., 2002. A Senior Manager’s Guide to Integrated Risk Management. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 14(4), pp.56–70.

Meulbroek, L.K., 2002. Integrated Risk Management for the Firm: A Senior Manager’s Guide. Available at SSRN 301331. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=301331.nMiccolis, J., and S. Shah, 2000, Enterprise Risk Management: An Analytic Approach, Tillinghast–Towers Perrin Monograph (New York).

Modigliani, F. & Merton H. Miller, 1958. The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment. The American Economic Review, 48(3), pp.261–297.

Modigliani, F. & Miller, M.H., 1963. Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction. The American Economic Review, 53(3), pp.433–443.

Myers, S.C. & Read, J.A., 2001. Capital Allocation for Insurance Companies. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 68(4), pp.545–580.

Nocco, B.W. & Stulz, R.M., 2006. Enterprise Risk Management: Theory and Practice. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 18(4), pp.8–20.

Pagach, D. & Warr, R., 2011. The Characteristics of Firms That Hire Chief Risk Officers. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 78(1), pp.185–211.

Samanta, P., Azarchs, T. & Martinez, J., 2004. The PIM Approach to Assessing the TRM Practices of Financial Institutions. Standard and Poor’s, a division of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. , New York, NY.

The Economist, 2015a. Reinsurance: Compacts of god. Available at: http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21652363-market-risk-changing-compacts-god.